Categories: All Articles, Our Oregon Heritage

The Condons

Thomas and Cornelia Condon, newlyweds, arrived by ship at Portland, Oregon on 3 March 1853, Thomas' 31st birthday. They came on the clipper ship Trade Wind, having survived a fire at sea 453 miles off the coast of Argentina. It was a 103-day voyage from New York City, around Cape Horn to San Francisco. The Trade Wind was a brand-new ship. Despite the fire in the hold which delayed them for a day, and despite being twice becalmed for two other days, the voyage of the Trade Wind was the 5th fastest made by any ship that year.

Thomas had attended Casenovia Seminary, and had recently graduated from Auburn Theological Seminary, both in New York state. He had sought employment as a minister of churches in New England, but at each interview, when it became known that he was Irish, the interviews ended. The Scotch Presbyterian New Englanders were much prejudiced against the Irish, who were considered “white trash.”

A friend advised him, “Brother Condon, you see what a prejudice there is here against your nationality. When next they ask where you were born, had you not better say that you had spent most of your life in New York or some other evasive answer that would be perfectly true?” Thomas considered the suggestion a moment and then answered, “Brother Delivan, if the Lord has any work that He wants me to do in the world it is work that an Irishman can do.”

Thomas applied to the Home Missionary Board of the Congregational Church, and was offered the position of being a missionary to the Oregon Territory. The Oregon Territory had officially only come under the ownership of the United States just six years before, in 1846. Thomas was qualified to be a missionary in every respect but one. He was unmarried. A missionary being sent to Oregon must be a married man.

Thomas went to Cornelia Holt, a young school teacher that he admired, and asked if she would consent to marry him and accompany him to Oregon. Perhaps to the surprise of them both, she consented. They were married 31 October 1852, two weeks before setting sail on the Trade Wind. Cornelia's mother had died 11 years earlier, and her father remarried a year later. Her family ties were, therefore, not strong enough to prevent her from setting off on this adventure.

Thomas and Cornelia thus became our first Oregon connection.

Thomas Condon was born to John and Mary Condon in Ballinafana near Fermoy, County Cork, Ireland, 3 March 1822. Just a few miles from the crude limestone hut that was their home stood the Condon Castle, also known as Cloghleagh or Kilworth Castle It is an imposing 72-foot-high stone structure that dominates the countryside. It was constructed by the Condons following the Norman Conquest which took place in 1066. William the Conqueror granted the land to the Condons for the help they gave him.

The castle was built for defense. It is an architectural wonder. The Condons were amazing builders. Ireland has lots of castles that were built during this period, but the Condon castle is the only one still standing as firm as it was when it was first constructed. It is built on a big rock on a high spot above the River Funshion, a tributary of the River Blackwater. A tunnel under the castle leads to the river. If the castle came under attack, having a water supply would not have been a problem.

The stone walls are thick and tall, perhaps five feet at the base, and are still straight and firm after the passage of a thousand years. (How did the Condons get those stones all the way up there, Mac wonders?) The windows of the castle are mere slits through which the Condons could accurately shoot arrows at invaders without fear of being hit by return fire. The massive doors were doubled. If invaders were able to penetrate through the outer door they would find themselves in an entryway blocked by the second set of doors where the Condons could pour boiling oil or water on them from above.

If the invaders were able to penetrate through the second set of doors they'd find themselves on the ground floor where all of the Condons' livestock was sequestered. Attacking the Condons required ascending the winding staircase on the northwest side . The staircase spiraled upward in a counter-clockwise direction, and had no protective railing. This put the invaders at a great disadvantage because their left hands would have to wield the swords while their right hands were employed holding onto the wall to keep themselves from falling. The Condons, coming down the stairs, could hold on with their left hands while brandishing their swords with the right.

There were three upper stone floors supported by stone arches that are anchored into the walls. Between the stone floors were wooden floors that have since rotted away, necessitating the closing of the castle to visitors. It now belongs to the government. For nearly 1,000 years the castle was owned by only two families. The Condon clan maintained control until Oliver Cromwell wrested it away from them, and gave the castle to the Fleetwood family. The Condons briefly regained possession when one of them posed as a cobbler, was admitted to the castle, got the inhabitants drunk, and opened the doors to his compatriots. They lost the castle permanently in 1643. Thereafter the surviving Condons, like the rest of the Irish, became poor tenant farmers.

Here I must pause and tell the interesting thing that I just learned. Our brother, Tim, has an inherited problem called Dupuytren's Contracture wherein, over time, the last two fingers of the hand bend inward toward the palm until it becomes impossible to open the hand. Over the years he has had multiple surgeries on both hands to alleviate the problem. It occurs in men who are descended from Northern European (Scandinavian) ancestry. I had done extensive family history research, and assured Tim that he has no Scandinavian ancestors. I was wrong. My recent researches reveal that the ancestors of the Condons were Vikings who settled in Normandy in northern France. They crossed the channel with William the Conqueror. Tim's hands are confirmation that we do, indeed, have some Scandinavian blood, and that the Condons are the probable source.

Thomas fondly remembered his grandfather, Michael “Bebe” Condon as “a grand old man.” Thomas' father, John, was a stone cutter in the nearby limestone quarry. This is probably where Thomas' interest in geology began. His earliest toys were fossilized sea shells from the quarry.

John was a Protestant. His wife, Mary Roche, was Catholic. That probably made them unpopular with both groups. They were poor, had no future, and decided to emigrate to America with their three boys. Thomas was the eldest, at 11 years old. (A daughter, Mary, was born in America in 1836). They saved their money to buy ship's passage, loaded their few belongings into a wheelbarrow or little wagon, and set off on foot to make the 140-mile journey to the coast. Friends and relatives probably accompanied them partway, and probably contributed what money they could to help them. That's the way things were done then.

That was in 1833. They settled in what is now Central Park, New York City. Their coming to America at that time was fortuitous. They thus avoided the great Potato Famine that killed a million Irish in the 1840's, and caused another million to emigrate. Potatoes were the mainstay of the Irish diet when Thomas was a boy. It was all they had to eat during some seasons. When the potato blight hit Ireland there was nothing left for the Irish to eat. The English landlords refused to help. This was their way of clearing the land for livestock production. It was only in the year 2021 that the population of Ireland finally reached its pre-potato-famine level.

What language did the Condons speak? My researches reveal that both Irish and English were being spoken in Ireland at the time the Condons emigrated. The Irish language was being suppressed, and English was being encouraged. Very likely the Condons were not under the necessity of learning a new language when they arrived in America.

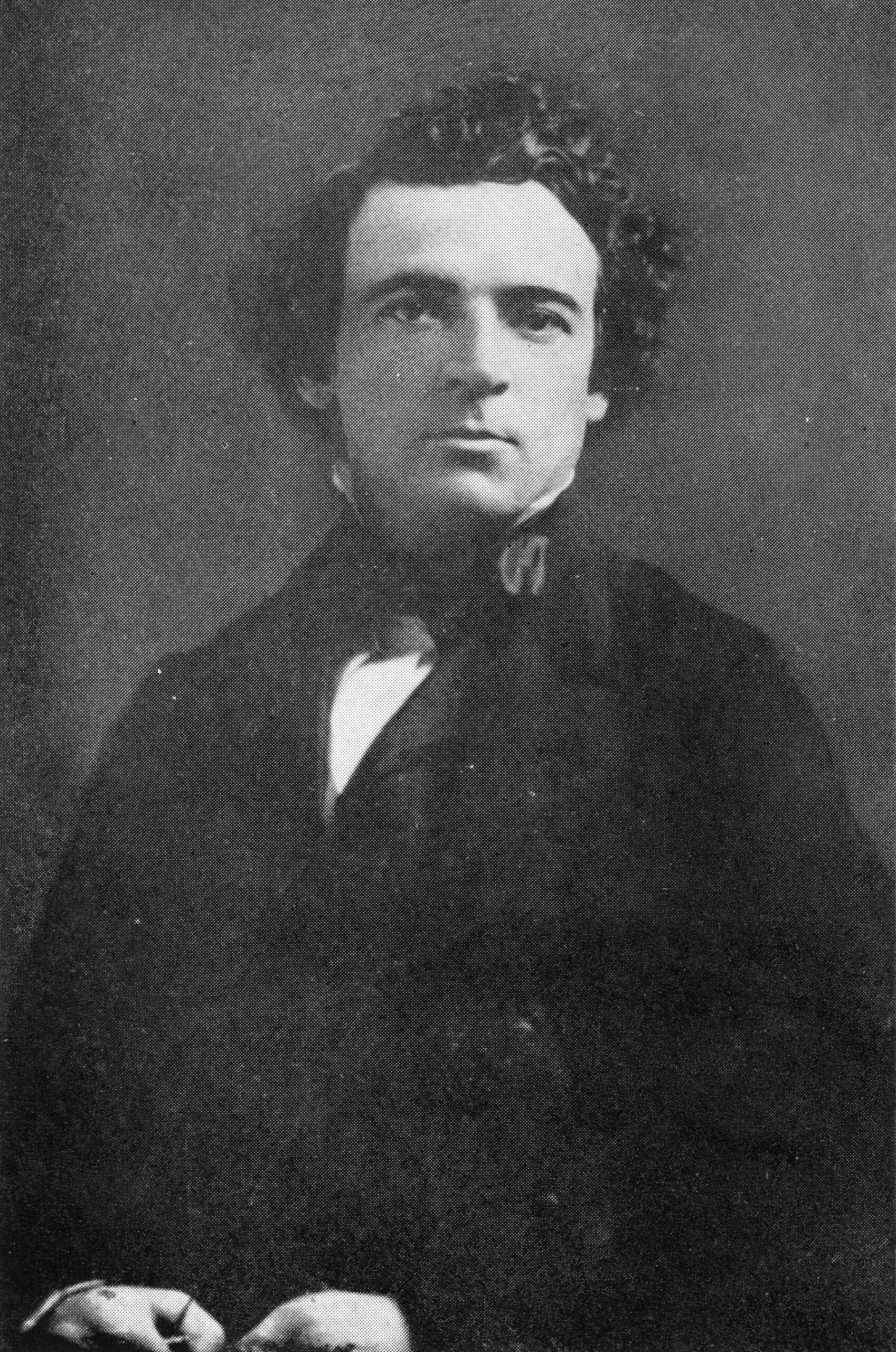

Thomas and his two brothers roamed free for the first year of their residence in America. Then Thomas went to work. He first worked for Miss Eliza Cox who raised flowers for the city market. “He was small for his age, but was strong and eager to learn, for he loved the flowers and cared for them most tenderly. His face was earnest and pleasing, with dark curly hair and bright brown eyes full of sunshine and courage. A warm friendship soon sprang up between the Cox family and the boy, and although he could not attend school, he studied his arithmetic evenings and, with the help of the family, made rapid progress. Here he spent two very happy years, and when he finally left her employ, Miss Cox gave him her own gold pencil, which he treasured throughout his life.” (Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist of Oregon, by Ellen Condon McCornack, pg. 6).

Thomas was next hired by Dr. McNevin, one of the leading physicians of New York. The family took him in as one of their own, made him their office boy, sent him on errands driving a horse and a gig, taught him drawing, and tutored him in algebra and geometry to prepare him to help in surveying the Erie Railroad. He enjoyed algebra, “but when he dipped into geometry his joy was complete. He said later: 'It lifted me to the clouds; I drank it in as a mental food.'” (Ibid, pg. 9).

Getting an education in Ireland would not have been possible. It wouldn't have happened in America, either, had it not been for Miss Cox, Dr. McNevin, and Thomas' own inner drive to learn and to improve himself. He received his education at home and in the places where he worked. When he was 19 he and his father went “west” to Michigan to homestead and there his father died. Thomas returned to New York state. He attended a collegiate institution at Casenovia, New York, and then began teaching school at Camillus.

Here I will insert four stories that best reveal the character of this grandfather of ours:

“Camillus … (had) a strong debating society; and he was very fond of a good debate. One winter evening there was to be a noted debate at the Camillus school building and, being one of the principal speakers, he was eager for the fray. Something had detained him so that he was late in starting. He had just reached the foot of a long slippery hill when an old lady called to him. 'Oh, Thomas, you are just in time to help me up this steep, icy hill. I could never make it alone.' Right there he faced a strong temptation and fought a quick and fierce battle with himself. This delay seemed at first impossible, but the gentleman won; and he gave the old lady his arm and slowly walked by her side up the long icy way. He entered the school house believing that his evening was spoiled, but found that the storm had so interfered with transportation that one or two out of town debaters were also very late, and he was in time after all.” (Ibid. pg. 10).

I pair that story up with this next one which took place on the Columbia River in Oregon. Thomas' kindness to women and to downtrodden people carried over to Oregon and stayed with him throughout his long life. He knew what being persecuted, and what being looked down upon, felt like.

“At the close of one of (his) frequent visits to White Salmon, Mr. Condon with others had been waiting under the cottonwoods for … the river steamer. … When finally it was hailed and after much swinging and backing and churning of water it was stopped broadside to the sandy river bank, the long, slender gangplank was made fast and the passengers quickly passed over the intervening water, using a tightly suspended rope for a hand-rail. Then the crowd looking down from the upper deck, saw an Indian woman start across with a pack on her back and carrying a heavy child. She had watched the others and had seen the teetering and bending of the slender board. She was too badly loaded down to control her own movements. She was sore afraid, stopped and drew back. If she had been a white woman any deck hand would have offered to carry her child, but she was only an Indian. Suddenly Mr. Condon darted down the plank to her rescue, reached out his arms for the little 'papoose' and carried it across; and the mother, thus relieved, made her own way to safety. The Indians were usually allowed to look out for themselves; but to him she was a woman, one of God's creatures and a mother, needing a helping hand, and his chivalrous nature saw no color line.” (Ibid, pgs. 33-34).

And then this story from his old age:

“Mr. Clifton Condon of North Hollywood, Calif. told me in 1959 about a visit his great-uncle Thomas made to his parents when he was a small boy … Boylike, knowing his uncle's interest in rocks, he went out and filled his pockets from the beds that covered the area where the cemetery is now, and brought them back to Thomas. The old man was in conversation with the adults, and they waved the boy off. He was not to bother the visitor, who already had more rocks than he knew what to do with!

“But Dr. Condon thought otherwise. Opening up his arms, he smiled Cliff closer and had him show him every stone, telling him about what they were, and thanked him kindly.

“Cliff Condon never forgot that one time he saw his famous uncle, and was always impressed by his genuine liking for children.” (Letter from Fred Morrow).

And finally, this story, about 1842, when he taught school in Skaneateles, New York:

“Here there lived a poetical wag who wanted to test the new teacher's ability and sent him a problem to solve in the following language.

“In the midst of a meadow well stored with grass,

I bought me an acre to feed my ass,

What length of rope will feed him all round,

On no more and no less than an acre of ground?”

“The teacher accepted the challenge, solved the problem and answered as follows:

“If in the midst of a meadow a pasture you'd take,

Whose area exactly an acre would make,

X feet of rope

Would just about give your due I should hope.

But your horse you must tie close by the nose,

Else all this our poetry better were prose.

For if for a holder you'd take his hind leg

The further, of course, he'll roam from the peg;

And you'd be to blame your friends thus to bother,

Besides cheating your neighbor who sold you the fodder.”

(Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist of Oregon, pgs. 10-11).

The Trade Wind set sail from New York on 13 November 1852, and headed south toward the equator. The trip was financed by the American Home Missionary Society . Winter would not as yet have settled in. The ship reached San Francisco in late February of 1853. Thomas and Cornelia, therefore, spent most of the months of December, January, and February in the southern hemisphere, and thus missed winter altogether.

It was a very pleasant voyage, except for the day of the fire. The fire started beneath the bricks on which stood the massive stove. Smoke billowed out of the hold. Bucket brigades were formed by the passengers. One after another of the crew went into the hold to fight the fire, only to be overcome by fumes. At one point 16 crewmen were laid out on the deck with the female passengers working over them to revive them. As soon as one would revive, he would dive right back into the fight. It was touch and go for some time; and when at last the fire was out, everyone fell exhausted on the deck. An examination of the ship revealed that no structural damage had been done, and the captain elected, with the approval of the crew and passengers, to continue on.

The 103-day voyage took them to San Francisco where the Condons spent a day waiting for a steamer, the Oregon , to take them on to Oregon. Four more days of sailing brought them to the mouth of the Columbia River. They debarked at Portland March 3.

Upon reaching Oregon Thomas and Cornelia first settled at St. Helens, Oregon, a small community on the Columbia River. Here Thomas began his missionary work and organized his first Sunday services. He was to be paid by the American Home Missionary Society, but the pay was meager and not adequate. Thomas, therefore, also opened a school where he could teach the local children, and be paid tuition by their parents. Every third Sunday Thomas also took church to the people at Scappoose, nearly eight miles away. Presumably he walked.

Thomas and Cornelia found a place to live, but had no furniture. Thomas built what they needed. Together they made a mattress and stuffed it with moss Thomas gathered from the trees.

Following is an excerpt from a letter that Thomas sent as a report to the Home Missionary Society:

“St. Helens is built on a bluff of porous volcanic rock, on the banks of the Columbia, 80 miles from its mouth and 20 below that of the Willamette …

“We came here, found a hearty welcome which has not grown cold, and trusting that in it God was giving us a promise of future usefulness have worked in our humble way cheerfully.

“We found a village of some 20 families, with no public building other than a nine-pin alley and a bar room; there was no school house and no school.

“Upon our arrival the proprietor of the claim on which the village is situated was preparing materials for a school, and soon erected, at his own expense, a pleasant and comfortable building, large enough to accommodate our congregation.

“In this building we meet for worship on the Sabbath and in it we have a school of 20 scholars through the week. Our Sabbath congregation has steadily increased and thus far has been composed of attentive hearers.”

In his next report he stated, “A good part of the adult population of our neighborhood, and all the young who are old enough, attend our Sabbath services. Our Sabbath school continues to be well attended; it numbers 25 children … Some weeks since I presented the subject of Temperance to our people in a Sabbath evening lecture. The next day the proprietor of our tavern called us in to witness the closing scene in his bar room, and since then our only tavern has been a Temperance one. … The nine pin alley has also been closed, and our village now presents a more orderly appearance. This is especially so on the Sabbath, as compared with Sabbaths six months since.”

Their first baby, Edward, was born at St. Helens on 3 December 1853. He grew to be a very promising young man in whom Thomas put a great deal of trust, love, hope, and training. He was Thomas' protege, sharing his interest in fossils and geology. Unfortunately, Edward became ill, and died at the age of 18. His death was a heartbreak for Thomas and Cornelia.

Our great grandmother, Ellen, their second child, was born at Forest Grove, Oregon on 13 August 1855. Ina was next in 1857, born in Albany, followed by Seymour in 1860, also born in Albany. Mary Cornelia Condon was born 16 August 1862 in The Dalles, but only lived three months. The next baby, Aubrey, was born in 1865, and died at the age of six months. Next came a set of twin girls, Clara and Fannie, born 1866 in The Dalles. Fannie died unmarried at the age of 31. Baby Jane was next, born 1867. She died at the age of five. The last child born to Thomas and Cornelia was Herbert, born 1870 in The Dalles.

Thomas and Cornelia had 10 children. They lost three as small children, and two as young adults. The other five married and gave them 24 grandchildren, not all of whom lived to adulthood.

From their start in St. Helens, the Condons were in Forest Grove in 1854-55, then went up the Willamette by river steamer to Albany in October 1855. Thomas established congregations at each location, and continued teaching school children during the week. His ministering duties covered wide areas, and there was much to do. He did a lot of walking between assignments, but also sometimes needed to take horse and wagon. When the creeks were swollen with rain water or melting snows, crossing them became treacherous. Thomas had to urge the horse into the stream. As the water deepened, the horse had to swim, and the wagon floated and was being carried downstream. His children remembered the relief they felt each time the horse's feet could finally touch bottom on the far side of the stream, and could draw the wagon out of the creek.

Thomas' missionary activities at St. Helens, Forest Grove, and Albany were failures. His efforts at St. Helens failed because shortly after his arrival there, the steamship company decided that Portland would make a better seaport than St. Helens. The company pulled out, and the 20 families that had originally been there quickly dwindled to six. His efforts at Forest Grove failed because he found the ministers and churches there in hot debate and competition for members among a population that was largely indifferent to religious affairs.

At Albany he eventually lost his preaching position because of the issue of slavery. A majority of the white settlers south of Salem were from Missouri and the border states. They were very pro-slavery. So was the Democratic Party, which was dominant in Oregon politics. Thomas was very anti-slavery. His little congregation split over the issue. Oregon became a hotbed of debate over the slavery issue following the Supreme Court's decision in the Dred Scott case in March 1857. In that case the Supreme Court ruled that African Americans were not, and could never be, citizens of the United States; and that the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had declared free all territories west of Missouri was unconstitutional. Constitutional scholars consider the Dred Scott case the worst decision ever rendered by the Supreme Court. Oregon was on the verge of being declared a state, which took place less than two years later. Tempers flared as the citizens argued over whether Oregon should be declared a free or a slave state.

Nor was slavery the Condons' only problem. Following is an excerpt from a letter Thomas sent to the American Home Missionary Society, written from Albany:

“There is just now much disturbance to the ordinary ongoing of our affairs. … Our young men have left to defend our frontiers against hostile Indian tribes, leaving this valley but a small supply of arms, and consequently much anxiety lest the enemy fall upon us in force through the unguarded passes of the mountains. … The savages are in arms on every side of us, they hate the whites and do not hesitate to threaten his extermination. We are therefore in danger.”

Supporting his family and keeping them fed was perhaps Thomas' greatest worry. Another letter to the A.H.M. Society stated, “Living here is more expensive than where we last lived. Clothing and groceries are much more expensive than at the north. … I have not yet received anything from your office this year.”

Things were expensive because men were leaving their farms to have a fling at mining, and prices went sky high.

An agent for the A.H.M. Society visited the family at Albany and reported, “A long shed-barn, roughly partitioned and rudely furnished, constitutes the sanctuary of his home, station, and schoolhouse.”

Getting his salary from the American Home Missionary Society back east was tenuous. Teaching school was necessary in order to give the family a little income. The A.H.M. Society did not approve of such extracurricular work. Thomas defended his school teaching by telling the A.H.M. Society secretaries that the westerners expected a minister to follow some other occupation toward earning a livelihood and looked in scorn upon a mere preacher as a parasite. He insisted that his own personal circumstances demanded that he teach, and that, in fact, his own community insisted that he teach.

“Both your letters speak your wishes respecting my connection with a school. My intention again, as it was at St. Helens, has been to make so much teaching as would not seriously hinder my work as a pastor, the means of relieving your society of the burden of my support, for in Oregon I cannot see even a remote chance of our pioneer generation of ministers being sustained by its own people.

“...The church may and ought to use the schools as a means to collect within her reach those who seek an education in this land … For such how natural to think of church near a school and a school near a church: the school to give life and energy to the church by bringing the work to her very door; the church to shed a halo of religious influence over the school, bringing weekly prayer meetings, lectures and monthly concerts within the reach of the young. … When a minister of our connection opens a school the youth come several miles to attend it. … We took a few children to board: from the care of them Mrs. Condon saved enough to aid materially. … In conclusion I would say that as soon after learning your wishes as I could I closed my school and shall with the blessings of God, henceforth devote to my pastoral duties more time than I have yet had to give them.”

Thomas decided that there were probably greater missionary opportunities east of the Cascades. Reverend Tenney, in The Dalles, resigned his position, and left, saying that The Dalles was the hardest place he'd ever been. He wrote that he did “not know of five living active Christians in any denomination” out of 500 people. Thomas purchased Reverend Tenney's house, sight unseen, in The Dalles so that his family would have a place to move into when they arrived. A hard winter set in before the Condons could leave for The Dalles. I quote now from Ellen Condon McCornack's book, pgs. 22-23:

“The memorable winter of 1861 and 1862 was nearing its close. It was the winter of December floods, when the river-boats steamed over the rich farms of the Willamette Valley, rescuing the frightened mothers and children and anxious fathers from their own house-tops or upper windows; when barns went drifting down stream carrying their freight of fowls and lowing cattle. It was the winter of deep snows and ice blockades, but, as spring approached, a trial trip up the Columbia had proved the possibility of reaching The Dalles in spite of drifting ice. To be sure, the snow was still ten feet deep at the Cascades, but those were pioneer days, and the first through boat carried among its passengers Mr. and Mrs. Condon and their four children, who had been waiting for the opening of navigation on the Columbia.

“On account of drifting ice this first trip occupied parts of two days, making it necessary to spend the night at the Cascades. The next morning found our passengers 'Crossing the Portage' around the surging rapids of the Columbia Gorge. They did not travel in an electric car, nor even behind a steam engine, but in a crude conveyance covered with black oil cloth, drawn by mules on a trolley track. This primitive car line was on the south side of the river and at this time was all there was of railway transportation in the state of Oregon. A few months later the mules were replaced by the historic 'Pony Engine,' which carried 'millions of golden treasure down stream, earning its weight in gold.'

“… At the Upper Cascades another boat of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company was waiting to carry the travelers fifty miles further up the great Columbia. Finally, having reached The Dalles, Mr. Condon was very much surprised to learn that the house he had recently purchased was already filled by three families and a bachelor. The little town was full to over-flowing, and families were indeed fortunate to find comfortable shelter until they could build their own homes. Gold had been discovered in eastern Oregon and southern Idaho, and there was a mad rush to the mines.”

The Dalles was the only town east of the Cascade Mountains. It “was a tough town full of desperate characters. Shootings and stabbings occurred daily, and horses were not left unwatched day or night. The gold rush was soon over but The Dalles was never a place of preponderant righteousness.” (Gentle Thomas, an address delivered 1 March 1959 by Fred R. Morrow). One writer said that The Dalles is a town with “more activity in a day than Portland in a month.”

The town changed for the better while Thomas was there. Some of the change was due to the decrease in mining activity, and due to the more lawless elements going elsewhere; but surely a good part of the change was due to Thomas' gentle influence. A note from the Congregational Church records a decade later says, “The town is much more quiet on Sabbath than formerly—the stores being neatly closed, and the people as a general rule, attending church and sustaining the institution of Christianity.”

Thomas' “Congregational flock met upstairs in the courthouse, directly over the jail from which sounds and odors wafted upward through widening cracks in the floor.” He immediately accepted the challenge of raising enough funds to construct a genuine church building. He successfully raised $1,000, and the building was ready for use by January 1863. It was located on Third St. between Washington and Federal.

Everyone liked the Reverend Condon, including the gamblers and saloon keepers. Their children attended his Sunday School. One evening the children put on a program to which all of the parents came. At its close a saloon keeper asked to speak. He said, “The Sunday School is doing a good work; we saloon men like it for our children; we believe in it and want to help. Now, Vic, let's take up a collection. You take your hat and go down that aisle and I will take this side.” (Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist of Oregon, by Ellen Condon McCornack, pg. 27).

“During these early days in The Dalles when the town was still full of professional gamblers and while they as yet seemed unashamed of their occupation, they adopted a certain fashion of overcoat which was well known as a gambler's coat. Some wag among them proposed that they make the new minister a present of one of these elegant overcoats. They enjoyed the prospect of the joke and appointed one of their number to make a presentation speech; then met the minister by appointment and in a very gentlemanly, appreciative address presented the overcoat. It was intended to be very long, reaching almost to the heels. It was of rich dark brown material, elegantly trimmed with a lighter shade of brown fur. Of course Mr. Condon saw it was a practical joke, but it would do no good to resent it; so he thanked them in the same kindly manner in which they had made their presentation. Then looking at the handsome garment he spoke with hesitation, as if in doubt, as he said naively, 'I think I can teach that coat to behave itself.'

“Mrs. Condon came to the rescue by removing the fur trimming from across the bottom of the coat and making it ten or twelve inches shorter. In this way the minister wore the coat several years, and it is safe to say that no garment ever had a better reputation than that gambler's overcoat. Perhaps it was because they felt a little ashamed of their joke, or perhaps only because it served as an introduction, but the gamblers were always among his warmest friends.” (Ibid, pgs. 28-29).

The Dalles was the key that unlocked Thomas' interest in geology and fossils. Military patrols went to the John Day and Malheur Lake areas, found fossils, and brought them back to Thomas. So did the teamsters who took supplies to the mines in eastern Oregon. After the Civil War ended, Thomas obtained permission to accompany the cavalry on a trip to Harney Valley with a return by way of the John Day Valley. He returned with many specimens.

Thomas made many trips to the John Day country. Soldiers were assigned to guard him while he was at work, but he was reportedly so enthusiastic about the fossils, that soon there was no one standing guard. The soldiers were all excitedly crawling around on their hands and knees looking for fossils. Today there are three national monuments in the John Day Valley commemorating the work that he did there.

Thomas was a minister without a place to study. Typically, he would take pencil and paper and his geologist's pick and hammer, and roam over the hillsides preparing his talks and lessons, and examining rocks and outcroppings.

“As he came down from the quarry one day carrying his geologist's pick and hammer and a large hand specimen of rock, he found a stone mason at work preparing a block from the quarry for building purposes. He stopped suddenly and holding up his own specimen, said: 'Gaylor, what would you think if I should give this piece of rock a blow with my hammer and find a spray of leaves on the inside?' Gaylor stared with incredulity as Mr. Condon placed his piece of rock on a solid foundation, carefully studied its probable line of cleavage, struck a quick sharp blow and the two sides fell apart, revealing a beautiful spray of leaves. He, himself was delighted with the result, but when he looked up with a smile into the face of the stone-cutter he found him white with fear and astonishment; for to him it was nothing short of a miracle. No explanation seemed to relieve the poor man's superstition, and he could never quite forgive the minister who was in league with the spirits.” (Ibid, pgs. 27-28).

In the summer of 1868 Thomas exchanged pulpits with Reverend Gray of Astoria which gave his family a change, and which gave him the opportunity to make the studies which resulted in his important geological paper “The Willamette Sound.” That fall he began giving weekly lectures on ancient history, and used the fossils that he had collected as visual aids.

Thomas kept a well-organized cabinet where he displayed his best specimens. It was a valuable, one-of-a-kind collection. It was visited by many notable geologists from back East, with whom Thomas corresponded.

“ During (the) busy summer of 1871, a Portland minister called at Mr. Condon's home accompanied by a representative of one of the great eastern colleges (Yale) who wished to purchase the Geological Cabinet; but he found the Oregon Collection was not for sale. The offer was liberal and the callers persistent, but neither gold nor persuasive eloquence could influence the owner to consider the proposition. Finally the Portland gentleman became impatient at what seemed the folly of an enthusiast. 'Why, Mr. Condon!" said he, "how can you refuse? Here you are a poor minister with a family to educate, and your wealth centered in this great collection crowded into a common wooden house. Don't you know a fire at any time may destroy it all?' But even threatened disaster could not prevail and the discouraged callers finally took their leave.

“The day so full of care was over and the night was gladly welcomed for its quiet hours of rest and thought. The offer for his cabinet had been so unexpected, and so persistently urged, that he had found himself taking the defensive without stopping to analyze his decision; and now in the quiet night, he asked himself whether he had been hasty, whether there was more sentiment than reason in his determination not to sell. As he reviewed the history of his geological work, its relation to his family and society, he found his judgment fully sustained his decision. In the emergency he had acted from an intuitive conviction, itself the result of years of quiet, half-unconscious thought. Yes, he had cold financial reason on his side, but it was always warmed and uplifted by the enthusiasm of his love. Besides to part with the collection would seem almost like shattering his own personality, of which it had become a part. Did not each specimen have its own identity, its own personal story known only to himself?—and yet, after all, the caller was right; a fire might destroy it any day. Then the thought of fire so took possession of his tired nerves that he could not rest. Finally he grew indignant at his own useless worry; he resolved to plan for the danger and then put all thought of it aside. He remembered a large tank of water beside the hydrant, some discarded carpets, boards, and timbers within reach. He planned what to do if a fire should break out down town, with the summer wind from the west. Finally, when every detail had been thought out, the tired minister fell asleep.

“A few days later, while the family were at their noonday meal, the fire bell rang, and Mr. Condon saw a column of black smoke pouring from the old 'Globe Hotel' several blocks away. There was a stiff breeze from the west, and remembering his midnight plans, he immediately began work upon the scaffolding. It was barely finished and he was spreading the (wet) carpet upon the roof when he turned to find the flames sweeping through the next block. The fire had fanned the breeze into a gale, everything had melted before the fierce heat, cinders were already falling around him and a wall of flames was surely, swiftly coming on. In a moment twenty men were running to his help. And how they worked! The roof took fire, one man fell prostrate from the heat; but the heroic work, the vacant lot on the west, tall trees close to the house on the east, and thorough preparation—all helped; and those who had time to note the progress of the fire saw it burn almost everything near, even the tall factory beyond, and yet the little house of wood stood unharmed in its setting of charred and blackened trees. When it was all over everything was found in confusion, many things had been carried out only to be burned, and worse than all, the shelves that held the cabinet were almost bare. Most of the choicest specimens were gone.

“Late in the day, when the scattered people had again gathered at their homes and the homeless ones were sheltered, Mr. Condon began holding a reception which lasted many days. First came a sturdy blacksmith carrying a fine oreodon head. 'Well, Mr. Condon,' said he, 'I am awful glad you were not burned out.—Yes, I lost everything, house, shop, and all. My little boy heard your house was on fire, so he rushed in and got this stone head. I don't see how he ever got away with it for it's awful heavy. He said he was bound to save something for you and he always liked this head with its fierce looking corner teeth. Once he stepped on a cinder and most dropped it but I guess it's all right.' Then a young man called to leave a box of horse and rhinoceros bones and teeth that he had saved. Still later came a little blue-eyed girl with her gingham apron full of beautiful sea shells. She said: 'I could not bear to have them burned up, so I just took those I liked best and carried them in my apron for you.' Finally, just at dark, came a small boy bringing home the head of a fossil dog. 'You know, Mr. Condon, you showed me your rocks one day and I liked this because it's a dog. So I just saved it for you.' Day after day they came until nothing seemed missing except a little cube of amber in which insects were entombed and after weeks had passed even this was found in the street. It is not strange that this tribute of affection made a new and tenderer tie between him and his people.” (Ibid, pp.125-129).

(A footnote in Ellen Condon McCornack's book says: "It is a historic fact that most of the finest specimens were carried away,—many of them by children, and that they were carefully returned within a few days.")

That story speaks volumes about Thomas Condon as a man and about the high esteem in which he was held by all who knew him.

When Thomas began his ministry at The Dalles in March 1862 he found seven “communicants,” five male, and two female. His congregation increased from 20, to 25, and then to 60 by August. In November there were 70 attending. By March there were from 100 to 150.

Thomas also started a Sabbath school in March 1862 with 8 or 9 children. One year later there were 60 or over. By December 1864 there were 80-90 children with 14 or 15 teachers. By the spring of 1870 the Sabbath school had “273 scholars and teachers with an average attendance of 216.”

On 15 April 1865, with the Civil War ended, and on the same day that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, Thomas proudly wrote the following to the American Home Missionary Society: “Could not think of asking further aid from the A.H.M. Society just now, and therefore persuaded the church to relinquish its dependence on help from abroad. We shall not therefore renew this year our application for aid … We quietly and gratefully drop overboard the line by which you have towed us on our way … And now dear friends, as we cast off that line and swing clear, we sincerely pray that you may be blessed … My accounts with you will close with the first day of April 1865.”

Thomas tried to end his financial dependence upon the A.H.M. Society at that point, but the effort was premature. The Dalles was entering a depression due to a winding-down of the gold rush, and people were leaving. The church soon had to make another request to the A.H.M. Society for $600 to pay half of the salary promised to Thomas.

Finances were ever a problem for him. “The income Condon received from the Society and from the church at The Dalles was insufficient to underwrite his family needs and his exploratory trips into The John Day country and to other areas of intense interest to him. Occasionally some interested person or group made up a purse for his use; but during his twenty years of missionary service, Condon was never free from worry over his flattened purse.” (Thomas Condon of Oregon, A Man with a Mission, by Egbert S. Oliver, Emeritus professor of English, Portland State University, 1983).

Thomas and Cornelia stayed in The Dalles 11 years, from spring 1862 to 1873. Moving became necessary because, as Thomas wrote to a friend, “three more of my children need to go away to school,” and because the Oregon state legislature had just offered him the new position of Oregon State Geologist. They returned to Forest Grove, which city had high hopes of being chosen as the site for the founding of a state university. He there joined the faculty of Pacific University.

The Condons were in Forest Grove for three years. He was offered a job teaching at the new University of Oregon which was being opened at Eugene. He was one of the first three professors hired by the university. He responded to the offer with this letter:

Forest Grove, April 7, 1876

Dear Sir:

Yours of the 4th inst. was received last evening, informing me that the Board of Regents had elected me to the chair of Natural Science of the State University. It gives me great pleasure to assure you that I cordially accept the post you thus tender me ...”

Sincerely yours,

Thomas Condon

Thomas Condon was a popular professor at the university. The students loved him. His lectures were enthralling. So were his field trips to beaches on the coast and to other places which were eagerly attended by non-student members of the community as well. The university required him to have a textbook for his geology class. To be obedient, he recommended one to his students, but told them not to buy it because he wouldn't be using it. Instead, he lectured from his geology cabinet, using his fossils in place of a textbook.

At the university Thomas taught chemistry, physics, geology, and all of the sciences. He was said to be “one of the most beloved personalities in Oregon,” and “the best educated man in Oregon.” (Oregon Public Broadcasting video, “Thomas Condon: Of Faith and Fossils, 30 min.).

It should be pointed out that this “best educated man” was for the most part self-taught. What little formal education he had received was mostly all ecclesiastical learning at the seminaries he had attended in New York. Many people would think that such an education would have been in conflict with what he was learning from his geological studies, but he said, “The church has nothing to fear from the uncovering of truth.” He embraced truth wherever he found it. The geologic record confirmed, rather than conflicted with, his religious faith.

Ellen Condon, Thomas' daughter and our great grandmother, attended the University of Oregon, and was a member of its first graduating class. She was the valedictorian of a class composed of four men and one woman. That was in 1878. In 1879 she married Herbert Fraser McCornack. In 1928 she published the book Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist of Oregon, from which I have taken many quotations.

Thomas stayed associated with the university nearly up to his death. He taught there for almost 30 years. His collection of fossils is now displayed at the university's Museum of Natural and Cultural History. In September 1895 “The Morning Register, Eugene's third newspaper … ran a two-page spread on the university and its professors. Of Condon it wrote that his 'vital teaching has long been the glory of the institution.' Unlike most men he 'grows young as the years gather about him, and his youthful energy and enthusiasm are every year more inspiring to his classes.'” (The Odyssey of Thomas Condon, by Robert D. Clark, pg. 401).

It was also said that, “For 20 years or more he was probably the most popular and most widely known public lecturer in Oregon.”

“Condon was the pioneer developer of Oregon geology, without peer in the work he was doing. He is remarkable not only as the discoverer and developer of the reading of the geological past in the fossil remains of this area, but also as the popularizer of this difficult subject through his pleasant, enthusiastic, honest and forthright quality of character. He was a master at public education.” (Thomas Condon of Oregon, A Man with a Mission, by Egbert S. Oliver, Emeritus professor of English, Portland State University, 1983).

Thomas wrote a book which he entitled The Two Islands. It was published when he was 80. It was a book about the geology of Oregon, describing how in prehistory Oregon had begun as two islands separated by 300 miles of ocean. One of the islands became the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon, and the other became the Siskiyou Mountains in southern Oregon and northern California. (The Odyssey of Thomas Condon, by Robert D. Clark, pg. 427).

“Cornelia … lived to see her husband's completion of his book, but not long enough to share his triumph in its publication. She was ill much of the summer of 1901, at the cottage on Yaquina Bay. Late in August she contracted typhoid fever. The children, notified that she was seriously ill, rushed to see her, Nellie from Eugene, Seymour from Oakland, Clara from The Dalles, and Herbert from Moscow, Idaho. Ina and her husband, Judge Robert Bean, were in Louisville, Kentucky, for a conference. They hurried home but arrived too late. Cornelia died at noon on September 2, not quite seventy years of age. 'She was a noble woman,' the Eugene Guard said, 'and had the respect of all.'” (Ibid, pg. 430).

“She was one of earth's noble women. The beautiful qualities of heart and mind, the sweet simplicity and tender modesty of her character endeared her to all who knew her well; yet, blended with these gentler attributes were the readiness to use her strength and voice in opposing wrong and the superb moral courage in defense of the right. A true woman of the hearth and home, impressive in moral integrity, saint-like devotion to truth and sterling Christian worth, her influence is far reaching and the world is better in that she lived and the memory of her pure life is an inspiration to the friends who loved her.

“And Mr. Condon, in his great sorrow, exclaimed: 'The light of my life has gone out.'” (Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist of Oregon, by Ellen Condon McCornack, pg. 345).

Though Cornelia was 10 years younger than Thomas, he outlived her by six years.

“After (Thomas') active, eager life had passed and failing health gave him ample time for retrospective meditation, he realized that he had lived through a grand period of pioneer history and remarked as he looked forward into the future in store for the rising generation: 'I do not know that I would exchange the rich chapters of my own life for all the future opportunities of these young men.'

“For he was the pioneer geologist who, by his own original research, caught a first glimpse of Oregon's lands as they rose from the ocean bed. He saw the sea-shells upon her old beaches; watched the development of her grand forest; saw her first strange mammals feeding upon her old lake shores; he listened in imagination to the cannonading of her volcanoes and traced the showers of ashes and great floods of lava. He followed the creation of Oregon step by step all through her long geological history and then entered with enthusiasm into the industrial and educational development of her present life.

“But above all, infinitely above all, he prized and labored for the noble character of her sons and daughters. Is it any wonder that his heart was full of gratitude to God for having guided him into such a rich heritage of life?” (Ibid, pg. 350).

Thomas Condon died at Eugene, Oregon 11 February 1907. He and Cornelia are buried in the Masonic Cemetery.

(Four other sets of our grandparents are there, also: Robert and Margaret Eakin, Andrew and Maria McCornack, Herbert Fraser and Ellen Condon McCornack, and Elwin and Bernice McCornack).