Categories: All Articles, Aspens, In a Grove of Aspens

Aspens

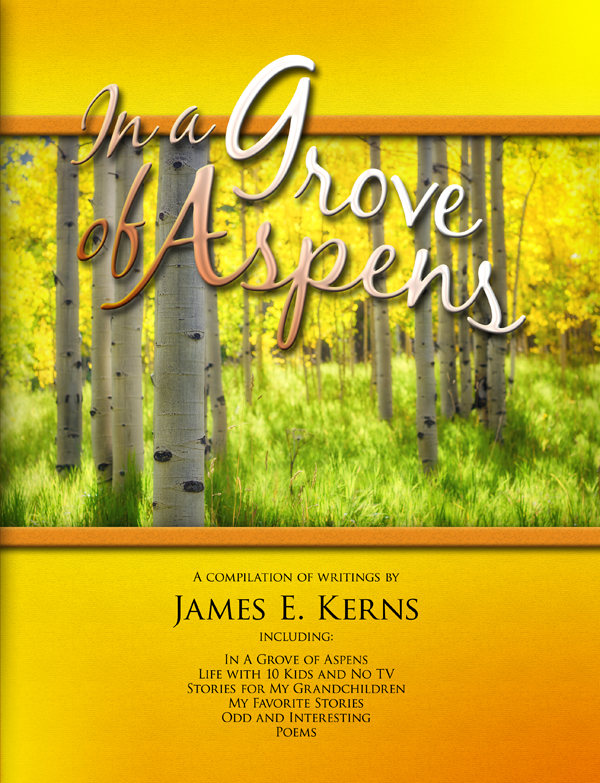

One of the instructional films used at the temple concludes with our father, Adam, exhorting us, his children, about what is truly important. He does it while standing in a grove of aspens.

As a little boy, one of my very favorite places to play was in a grove of aspens which occupied a narrow strip of land between Markle’s road and the irrigation ditch just below the site where my father eventually built his last house. The grove was thick—so thick that you couldn’t see through it. Most of the trees were saplings less than 3 inches in diameter. They were small enough that I, a small boy, could cut them down to make “logs” for the little, hidden cabin that I envisioned building there in the grove.

I had a safe, secure feeling while I was hidden in my secret places in the aspens. The grove was over a mile from my house, or I’m sure I’d have played there every day. Since that time aspens have always been my favorite tree.

Quaking aspens are beautiful trees. Even their scientific name, populus tremuloides, is beautiful and descriptive. I love how their leaves quake in the slightest breeze. The white bark and golden fall foliage make strikingly beautiful scenes against backdrops of dark evergreens. Everywhere I look in the fall I see settings just begging to be photographed or painted.

In the Shaeffer Creek draw are the largest aspens I’ve ever seen. Right beside the Triplet Tree (a spruce) is a grove of aspens which includes several whose trunks are two feet in diameter.

As a woodturner, I love aspen wood. It’s my favorite. It’s easy to turn, has a distinctive, pleasant smell, and turns out a nearly white product with an occasional dark fleck or red streak.

The most significant thing I’ve learned about aspens is that they’re the largest living thing in the world. A grove of aspens covering several acres of area is actually one organism. Shoots come up from the roots of the parent tree, and send out roots of their own which produce more shoots. This method of propagation might go on for miles. Each tree in a large grove of aspens is thus connected with every other tree through their common root system.

The human family is like that. Did the Brethren realize the significance of Adam exhorting his children while standing in a grove of aspens?

We as a human family are intertwined just like aspens. The parent tree sends up shoots and sends nourishment to those shoots while at the same time its roots go back to its own parent from which it also receives nourishment. The grandchild has a direct, unbroken connection to its ever-so-great grandparent, as well as a traceable connection to every other individual in the grove or family.

In high school I memorized a poem by John Donne that perfectly applies here:

No man is an island, entire of itself;

Every man is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main,

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

As well as if a promontory were...

Any man’s death diminishes me,

Because I am involved in mankind;

And, therefore, send not to know

For whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

My boyhood grove of aspens got bulldozed. The grove had begun in the unrecorded past with a single tree—an Adam tree—which multiplied until my father determined that the grove was worthless, and that the strip of ground could be put to better use. I silently let him bulldoze my playground without a protest, but mourned the passing of the grove.

At either end of the grove, however, Dad left a single tree—Noah trees. One tree was on a side of the fence where cattle always grazed around it. That tree’s shoots were always grazed off as soon as they came up, so the tree has grown there alone for decades. The other tree, however, is on a side of the fence where the ground is never disturbed by grazing, plowing or mowing. This Noah tree is busy at its task of repopulating its world.

As a teenager I thought that our yard needed a quaking aspen tree. I selected a small, straight tree, dug it up, and transplanted it in the yard north of our house. It was a Lehi tree. It grew there as I finished high school, went away to college, served four years in the U.S. Navy, married and had children. In 1974 we came back, bought the home place, and moved into the house I’d occupied as a teenager. The transplanted Lehi tree was then a tall tree with many strong, nicely-placed branches. My older children used it as their favorite climbing tree.

My growing family made it necessary for an addition to be put on the house. The only logical way for the house to grow was for it to expand toward the north. The only drawback to the plan was that my Lehi tree was in the way. I loved that tree, and so did my kids. It was with great reluctance that I cut the tree down so that I could begin the addition.

The Lehi tree sent out many shoots, but they were all mowed by the lawn mower. One shoot, however, came up 60 feet to the west in a corner of the yard—a nice location for a new tree. I carefully mowed around it until it grew into a good-sized tree. It in turn sent out shoots, one of which came up 80 feet south, in another corner of the yard. I allowed this tree to grow, also. My grandchildren are now climbing this one. It has several progeny which have escaped the mower and pruning shears.

Quaking aspen roots reach an amazingly long way. I’ve found shoots trying to come up on the opposite side of the house from the tree. If, like Sleeping Beauty and her family, we should all go to sleep for a few decades, this house in a short time would disappear within a grove of aspens.

It may have been 30 years ago, when Marjorie and I were regularly attending the Provo Temple, that the significance struck me of Adam’s exhorting his posterity while standing in a grove of aspens. The title of the book that I would someday write to my own posterity has stuck in my mind all that time. The subject matter has been percolating since then. I think it’s ready to come out.