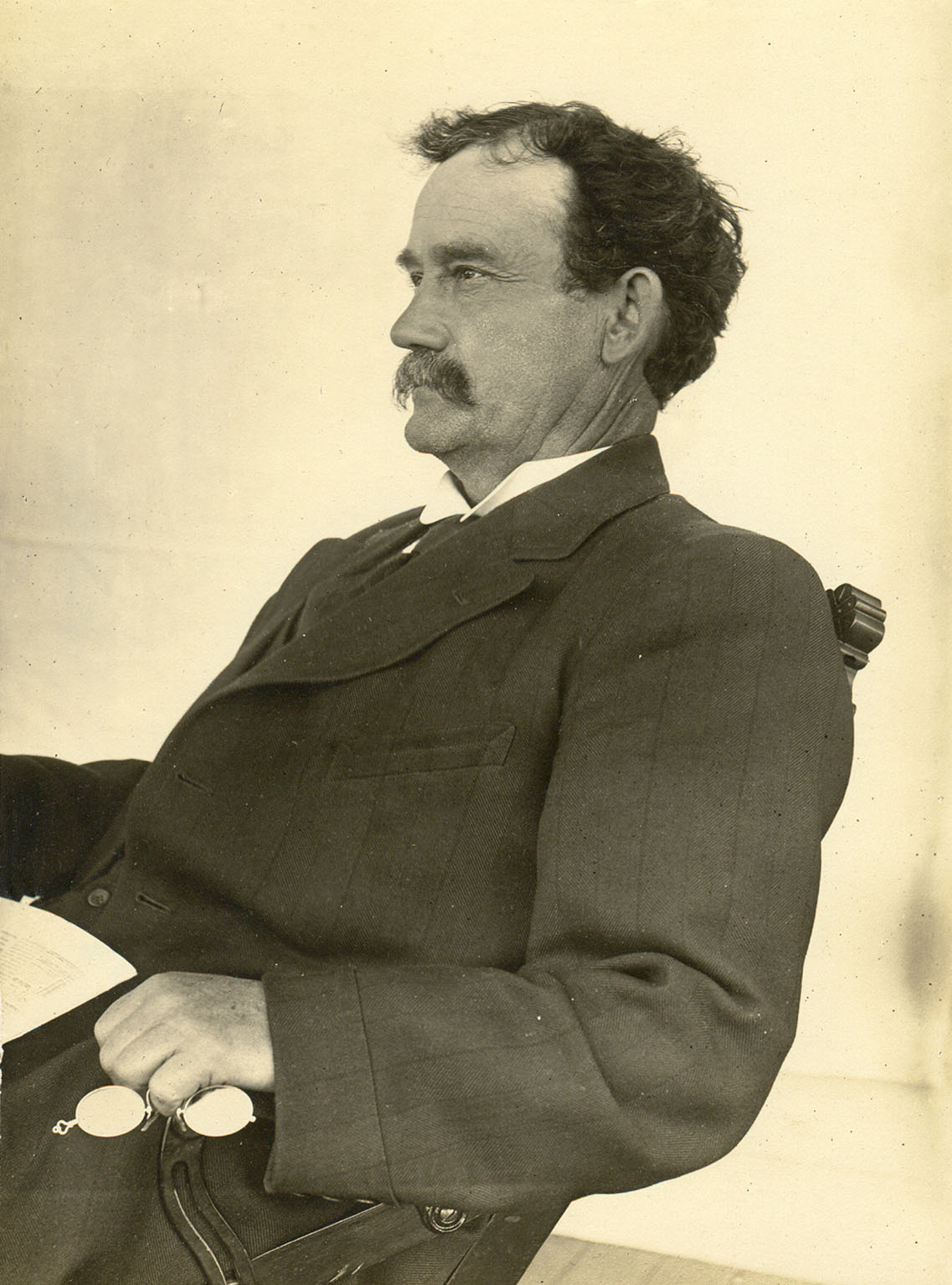

Herbert F. McCornack

The Country Doctor

When thinking of the life of the country doctor of seventy years ago one must turn back the clock quite a ways to get a true perspective of the life these doctors led and the conditions under which they worked. While anyone will admit that the greatest of the handicaps under which they carried on their profession, as compared with conditions surrounding present day practitioners, was unquestionably the lack of information and medicines the last half century has made available, much of the hardship of their practice was a part of that day and the times.

There were no hospitals available to them, no nurses, no telephones, no specialists to go to for advice, and the only transportation to their patients was by horse drawn vehicle over unimproved roads often well nigh impassable with washed out bridges, dangerous fords and sometimes deep snow drifts. Confront a doctor of this day with these conditions and see how far he gets. The following are just a few of the experiences of a country doctor brought down to us from the 1870's and the 1880's.

(The following are stories about Herbert F. McCornack)

Whenever a call came in by a rider who had come ten or twenty miles and reported someone in need of help, the doctor saddled his horse or hitched up his team and was on his way day or night, fair weather or foul. Perhaps the trip would prove unnecessary, perhaps a life was to be saved, there was no way of knowing from the meager report of the messenger, —a cowboy, a Mexican, or an Indian, —the answer came when the doctor got on the job.

Once after a long drive in the hills the doctor found a man who had been gored by a bull in a very serious condition. Surgery was imperative. There was no one to assist other than a Swede ranch hand. There were no lights other than tallow candles, but the doctor must operate. The horns of the bull had punctured the man's abdomen. Time was running against the patient. With the help of the willing Swede the doctor got the patient on the kitchen table. The Swede held the candle and the operation got under way. Suddenly the eyes of the stalwart Swede rolled upwards to the ceiling and both he and the candle slumped to the floor. The doctor found the candle where it had fallen, relit it, revived his helper and returned to his operation. The Swede was more than willing, but after hitting the deck two more times the doctor let him lie, stuck the candle up on a cracker box and completed the operation. Perhaps these men of the frontier came of a more rugged race, or perhaps they lived in a fresh sterile world where killing bacteria had not as yet become a scourge, but the man lived.

Another time a rider came from some distance reporting a rancher had been thrown from his horse and suffered a badly broken knee. After a long drive the doctor reached the ranch and found the man, attended by his wife, sitting up in a chair with one leg straight out before him pillowed on another chair. An examination of the pillowed leg indicated great soreness but no broken bones. The woman however insisted the knee was shattered and demonstrated by manipulating the kneecap which slipped about quite readily. The doctor asked her if she had examined the other kneecap. She assured him she had and gave him a demonstration on the other leg where the foot rested on the floor. The kneecap was rigid and in place. Recommending the application of Sloans Linament to the injured knee daily until well, and assuring them the man would soon be on his feet, the doctor unhitched his team for the long drive home.

A similar experience came one afternoon in the dead of winter. A soldier rode in from the fort some ten miles away reporting that the wife of an army officer had sent him to get the doctor to attend a sick child. After a ten mile ride through the snow drifts the doctor reached the river which was full of running ice. A boat met him at the riverbank, and after stabling his horse in a shed, he and his soldier boatman made a rather perilous crossing to the fort. As the doctor made his way up to the buildings he found the place all lit up and heard the fiddles going and the heels hitting the dance floor. The officer's wife who had sent for him was found on the dance floor and was very glad to see him. She told him her little boy had been fretful all day, and that while she did not know the child was sick, the party going on that evening was the big social event of the year and she wanted to enjoy it, a thing she could not do unless she had a doctor in whom she had confidence with her child. There was nothing wrong with the boy but the doctor stayed in attendance throughout the night and made the statement later that for his services that night he submitted the maximum charge.

Many calls were based on an emotional condition, like the one to attend the boy who wanted to eat his hands. Arriving at the farm home the doctor was taken to a bedroom where half a dozen strong men were gathered around the bedside of a big fourteen-year-old boy. The men were there to hold the arms of the struggling youth and keep him from carrying out his avowed intention of eating his hands. The doctor asked what the boy would do if his hands were released and was assured by those present that he would tear his fingers with his teeth. The doctor said that was something he had never seen, and after much persuasion induced the men to release the boy's hands. With a last terrific roar the boy shoved all ten fingers in his mouth at once almost choking himself and subsided.

Another emotionally based incident took the doctor to the home of three spinster sisters. Two of the sisters conducted him to the locked and guarded door of a room. They told him their sister had gone mad. They opened the door just enough to admit him and closed it quickly. The doctor found himself confronted by a big amazon of a woman, who in her rage and mental disturbance, had removed all of her clothes and had been cut on the neck and breast and was thoroughly covered with slippery blood. The doctor realized it would be like trying to handle a wet fish to take hold of her. As he entered the room the woman charged like an angry cow. The doctor said he had to think fast. As she rushed him he saw his only chance. As she came on him he seized her by the long hair of her head and slapped her down in a nearby chair so hard it nearly split the hickory bottom, and told her to sit still, which she did. As he washed away the blood and anointed her wounds he questioned her as to the cause of her mental flare up. Leaving her to dress, he went outside and delivered a scathing sermon to the other two sisters for carrying a family dispute and critism to the point of driving their sister mad. The doctor regarded his treatment as satisfactory, as the three sisters continued to live together under normal conditions.

The doctor was riding in late one night from a call in the country when a horseman rode up from behind and overtook him. As he pulled up his horse, the stranger uttered a series of unintelligible sounds and in the darkness seemed to point to his face. The doctor, reaching out towards the stranger's head, encountered something which felt like a blacksmith's iron punch. Further exploration revealed that it was a long slender steel punch driven into the lower jaw under a premolar tooth, as the doctor said, standing out like a boar's tusk, and looked like an interrupted extraction. He asked the man if he wanted the tooth out, and being given an affirmative nod, the doctor gave the extended punch a quick downward jerk, and the tooth popped out. Much relieved, the stranger began spitting blood and talking. His story was that the tooth was giving him great pain, and having no dentist at hand, he had gone to the crossroads blacksmith who was trying to get the tooth out when the pain became so great that the patient broke away and started for the nearest town. All the doctor got out of the encounter was a highly satisfied customer.

Some of the experiences of the country doctor took on a very grim side, as the days he lived in the shadow of the hangman's noose. The circumstances were these. A small child in the town was stricken with diphtheria. The stricken child was the son of a blacksmith, evidently a very ignorant man. As the child's throat continued to fill with the obstructing material, his condition became acute, and the doctor advised his parents that unless his throat cleared up he would have to resort to a tracheotomy operation, explaining to the parents that this operation consisted in opening the boy's throat and inserting a silver tube in his trachea so he would be able to breathe through the crisis of his illness. The father objected to the operation insisting that it would cause the boy's death, and that breathing the smoke from burning horse hoofs was the best treatment for diphtheria. However, as the patient got worse and the doctor had no faith in burning horse hoof trimmings, he opened the boy's throat and inserted the silver tube. When the townspeople heard that the young doctor had actually cut into the boy's throat, there was much indignation, and excitement ran high. People gathered in groups on the street and discussed the unheard-of act of the doctor. The most extreme thought the doctor should be taken out and hung at once. The more moderate advised waiting the outcome. If the child died, then they would be willing to join the lynching party. The doctor related afterwards that for days the situation was tense, and that it was with a feeling of much satisfaction and relief that he removed the tube and closed the wound.

Little Kenneth, three years old, playing with the knob off of his mother's umbrella let it slip down his throat. It lodged in such a position that it all but shut off the child's breath. Frantically his mother and a companion tried to extract it, and all the while as they worked, the little boy's face became darker and darker. A runner had been dispatched to the doctor's office, fortunately only four blocks away. By the time the doctor had covered the four blocks to the home the boy had all but passed out. Fortunately one look down the strangling boy's throat indicated a way to get a finger under the offending obstacle and lift it out. After being revived little Kenneth had just one statement to make, "Mamma tried and Auntie tried, but Uncle Dock got it."

One afternoon the doctor was riding back into town on his favorite horse. This little horse who he called Rosananti had been acquired from a Mexican who revealed nothing of his past history. It was a lovely day in early autumn, and the young doctor rode at peace with the world. All at once, as if coming from nowhere, the road from fence to fence was filled with charging cattle. A stampeding herd of perhaps five hundred head of half wild long horned Mexican steers. The cattle bore down on them at an unbelievable speed. The doctor's one idea was to get out of their way before they ran him down. His horse was dancing in what the doctor thought to be fear, until he sought to swing his head around for a race down the road away from the maddened cattle, but as he sought to turn the horse away from the onrushing tide the horse only whirled and pranced and held his ground. It was too late to leave the horse. To be caught on the ground in the path of those terrified cattle would be certain destruction. He sat his horse until the cattle were right on him when the horse whirled and raced across in front of the charging herd. The cattle were great rugged brutes with long curving horns which scraped the pony's sides and the rider's legs as they raced by. Any minute the doctor expected to find horse and rider in a mad pile up. Whirling at the far side of the road the pony raced back again always on the points of the onrushing horns. Back and forth they raced until the momentum of the herd was reduced and finally brought to a standstill. The handlers in charge of the herd rode up in great haste and congratulated the young doctor on the manner in which he had brought the stampeding cattle to a stop, and told him it was the finest exhibition of cattle handling they had ever seen. The doctor accepted their compliments on his splendid horsemanship, but when they wanted to buy his horse he turned them down flat. That little horse was not for sale.

The Little Boy and his Buckskin String

Of the five young boys in the McCornack family who trailed west in the covered wagons in the early eighteen-fifties Herbert was the youngest, just a year old as the family left their home state of Illinois. Grandmother thought that it was because he was confined to the wagon at a time when most children are learning to walk, later day specialists say it was an attack of polio that brought on the impairment, but when the little lad was two and three years old he had all but lost the use of one leg and of course had much difficulty in walking at all.

Grandfather and Grandmother were very busy people struggling to keep the family fed and shelter provided. The smaller children were left largely to the care of the older boys, and these older boys were very, very active youngsters. One day they went to the river for fish. Using a native Indian spear they succeeded in spearing and landing a salmon so large that not one of them could lift it. Walter, improvising a harness from scraps of buckskin, hitched a four horse team on to it, and with little Herbert running along behind as driver, they brought their big catch up to the house.

Another day, with their dog Coley, they foraged for blackberries. They disturbed a drove of wild hogs sleeping in the bushes, and the enraged hogs rushed the boys with such fury that they were glad to find safety on a big log drift beside the river while Coley fought the enraged hogs. In the struggle which ensued, Coley was able to get a strangle hold on a large boar; and notwithstanding the frantic struggles and squealing of the boar, Coley hung on until the hogs fled in panic into the woods dragging the little dog with them. It was only then that the boys ventured down from the log pile and pursued the trail left by Coley and the hogs. After following it some distance they came upon the body of the boar where the little dog, still hanging to its throat, had killed it. The boys had to carry Coley home as he had received a broken leg in the fracas; but the little dog was acclaimed a hero, and commended for his service to the family.

Still another day the boys ran into a herd of wild cattle, great long horned brutes, who attacked on sight, and precipitated some amateur bull fighting by Walter and Ed while Will and Gene found trees which they and little Herbert could climb. Again little Coley was in the forefront of the battle, and with the help of the older boys was able to drive the cattle away.

I fear I have wandered away from the subject of this narrative to some extent, but I bring in these incidents to illustrate the kind of life this little boy lived and how important it was that he be able to travel. Keeping up with his brothers with one dragging leg was the next thing to impossible. This was his problem. Determination and ingenuity became the answer. He found that by attaching a broad soft buckskin strap to the large toe on the impaired leg he could run by jerking the lagging leg ahead to complete each step. No doubt it was difficult to do at first, but he soon learned to hitchskip along at a pace which permitted him to keep up with his brothers. With use and activation the lagging leg improved, and within a year or so he had overcome all impairment and grew into a strong, able man. However, as a reminder of what he had been through as a boy, one leg always remained a bit shorter than the other and he walked with a slight limp.

I have always thought of this as an interesting story of pioneer times and of one little boy's determined fight against adversity. The story has more recently taken on new interest when I read an article on the most advanced methods of treating certain types of paralysis of the lower limbs, and studied a brochure featuring a recent scientific mechanism invented by two eminent specialists which may be attached to an immobilized member to assist in its reactivation. A careful study of the new device disclosed that it had nothing that the small boy's hand-operated buckskin string did not have. I call it an outstanding instance of native ingenuity and fortitude of a little boy raised in the wilderness. It is also an interesting fact that Uncle Dock, as his young nephews all called him, went on himself to become a skilled physician and surgeon.

The Wild Man of the Willamette

It was the early summer 1903. I was one of a party of surveyors working under a man from the Surveyor General's Office who had sent to Oregon to inspect the work of local contract surveyors who had bid on surveying sections of the public domain all over the hill country of Western Oregon. We were working our way up the middle fork of the Willamette River following the old Military Wagon Road, the only usable route across the Cascade Range between the North Santiam and the Green Springs Mountain Road east of Medford. As late as the turn of the century the settlers of that vast intermountain empire from Bend to Burns, Klamath Falls and Lakeview were still freighting in their supplies in four and six horse wagons. They had the choice of The Dalles, Eugene and Medford. These three routes were all unpopular with the freighters, but the old Military Road was looked upon with no more disfavor than the other routes, and all summer and fall hundreds of wagons with their sweating teams toiled up the heavy grades and through the virgin forests of the Willamette Pass.

In early July we worked our way by stages up the old road. It had not as yet been opened to traffic for the season as snow still lay in the higher passes and windfall timber from the winter storms still lay across the roadway. One day we moved camp five or six miles up the river and established a new base. It was a nice camping spot among the big trees on a flat beside the river. Tired from toil we turned in early and were soon sleeping soundly. The next conscious moment for me was when I found myself standing in the middle of the road, barefoot, in my shirt tail shivering in the cold mountain air, without the slightest knowledge of where I was or how I came to be there. The road where I stood was cut from the side of the mountain, and down over the grade far below I could see the white water of the river and hear its roar as it made its way between the rocks. My concern was, where was I and how come I was to be there? I recalled the new camp we had made the day before, but as I was facing the river bank as I regained my reason, I had no way of knowing from which way I had come. I was cold, and both physically and mentally disturbed. I gave serious thought to which way camp might be and finally turned right and started down the grade. I walked and I walked. In the semi darkness it was a rather terrifying experience, but I walked on and finally was filled with joy as I rounded a turn and saw the old covered wagon and the tents standing in the gloom. No mouse ever slipped into his nest as quietly as I found my bed and crept into my blankets. Morning came as mornings do, and the boss hailed us out of bed for breakfast and an early start. We were to go up the river a mile and cross to the other side where the boss had work for us.

At this point in my story I must go back to a further discussion of the Old Military Road and the use to which it was being put. Freighting continued late into the fall after the rains, and where there was no solid rock in the roadbed, great mud holes were worked up in the soft black soil. As these potholes stood and settled throughout the winter, the water drained out, and the surface became as smooth and as firm as the face of a pumpkin pie. As we headed up the road on that particular morning with axes, chain and compass, one of the leaders of the party broke into loud and startling profanity. His outbreak brought the entire party to an alert, and they gathered in some consternation beside one of these black pools, for there going straight into its otherwise unmarked surface and continuing all the way across were the tracks of a barefooted man. In the black mud the tracks looked huge, like the tracks of a giant. There was no little excitement over the find, and well might there be. For what manner of man would be roaming the woods fifteen miles from the nearest camp or habitation, barefoot and at night? "He is a wildman," said a voice. "He's not only wild but he's crazy," said another, "or he wouldn't walk through a knee deep mud hole when there is a mossy path on either side." A half mile up the road we came to the ascending grade with the river below which I recognized as the scene of my nocturnal visit, but I said nothing.

All the day long at every lull in the work conversation returned to the doings of the "wild man." He was spying on the camp. We would find all our provisions and much of our equipment missing when we returned. With guns and ammunition in his hands he would return in the night and massacre the entire party, for he surely was a madman. The day wore to a close. Eagerly the crew approached the camp and found everything in order. That night, however, the boys prepared themselves for the worst. Rifles were taken to bed and six guns were under the pillows, but morning came as usual. The all out call brought us all out from under our blankets, and as I stood up in my bed trying to get into my pants, the boss said with some emphasis, "Mack what on earth is the matter with your legs?" In surprise I looked down, and was I mortified at what I saw. Both legs almost to the knee were painted black with mud from the pothole. It was life's most embarrassing moment. There was no escape. There was no subterfuge. It was humiliating, but I had to confess. I was the wild man, and took a lot of ribbing. For many nights thereafter, though, I wore a short hobble, and took several good falls before I broke up the habit of wandering off at night to parts unknown.

The Cow Bird Story

To get the most out of this little story you should understand the life history of the cow bird. This little bird, smaller than a robin, builds no nest of its own, and raises no young. When an egg is ready to be laid, the female bird hunts up the nest of a blackbird, and deposits her egg in the blackbird's nest. From there on it is up to the foster parents; but being of a different species, the young cowbird has but little resemblance to his nest mates. The difference in appearance is quite noticeable.

Now in our family there is a strong family resemblance between the two older children, with a marked digression in the case of the third child, Andrew. The elder children often teased their little brother about this lack of family similarity, and when he would go to his mother for comfort, she would take him up in her arms and with a hug and kiss tell him he didn't have to look just like the other children because he was the one the cowbird left. Now little Janet didn't get the story quite straight, but she was quite ready to use it when it seemed to her appropriate.

When little Andy was two years old, guests were calling on his mother. She was called away to the kitchen leaving five-year-old Janet to entertain the company, a responsibility she was glad to assume. "We notice," said the guests, "that you and your older brother, Rodwin, are very much alike, there is a strong family resemblance, but your little brother here doesn't look like either of you." "No, he doesn't," said little Janet. "He doesn't look like us because he is the one the cow boy left." The guests so enjoyed the little girl's explanation that they told her mother upon her return from the kitchen, and poor Bernice laughed as hard as anybody.

My Father's Day and Mine

When my father was a young lad on the farm out west of Eugene he followed his father and four older brothers around the wheat field. Each carried a short steel sickle, and as the wheat fell from the blade, it fell onto the reaper's left arm; and when a sizable bundle had accumulated, the reaper bound it together with a wisp of the newly cut straw, dropped it in the stubble and swung his blade to start another bundle. Around and around the field, each reaper cutting right at the heels of the man next before him.

Grandfather and his boys were harvesting the grain they had planted that the family might be fed. They knew of no other way of getting the harvest in. All men harvested just as they were doing. There was no other way. Looking back from where we stand today we see that they were practicing the identical method used by the reapers who labored in the field of Boaz where Ruth the Moabitess gleaned. The picture was the same. Thirty one hundred years had passed without any change in this most essential and much used process.

When these bundles of wheat had lain out in the sun a sufficient time to cure and harden, Grandfather and the boys were again in the field, this time with oxen and wagons and hauled the bundles to the barnyard where they were piled in great weather proof stacks. Then when thrashing day came, the bundles were pitched down on the hard-beaten ground of the yard, and horses and oxen were driven around and around over the ground until the straw was separated from the wheat. Again we see the picture as no different than that of the Children of Israel thrashing out the grain on the thrashing floors of Pharaoh thirty five hundred years before.

And Grandfather had told his sons of the trip to America from Scotland just a few years before. How they had made the crossing in a wind-driven sailing ship. Just such a ship as had bourn the venturesome Phoenicians on their voyages into the unknown world of two thousand B.C.

Since those remote days the world had stood still with little change. Gunpowder, the printing press, yes, and a few of man's new ideas had come on the scene, but the progress of mankind and of the world was largely unchanged. It can truly be said that at the time my people came to the Oregon country the forward progress of man was still geared to the slow, measured tread of the oxen.

Note now the things which have happened in my father's day and mine. Things which were unknown to an earlier generation. The new things which have come about. The list is limitless. The harnessing and uses of electricity. An understanding of the world of bacteriology and its uses in protecting human life. The telephone, the radio, television, radar. The use of steam and the railways. Petroleum and its thousand uses. The airplane and its world-wide service. Each one of these innovations and a hundred more has stepped up the pace at which the world is moving from the four miles an hour tread of the ox to a fantastic speed much faster than that of sound. Why has all this come to pass in our time? Why was it that God in his infinite wisdom did permit the world to stand still for three thousand years and then in your time and mine pull the plug as it were and permit the world to rush to its full and final destiny? That is truly the sixty-four dollar question of our day.