Categories: All Articles, Our Oregon Heritage

The McCornacks

The Oregon Territory was acquired by the United States in 1846. Thomas and Cornelia Condon arrived in March 1853, becoming our first Oregon ancestors. As they were arriving in Oregon, the Andrew and Maria McCornack family was in Elgin, Illinois, 40 miles west of Chicago, preparing to start their own journey to the same place.

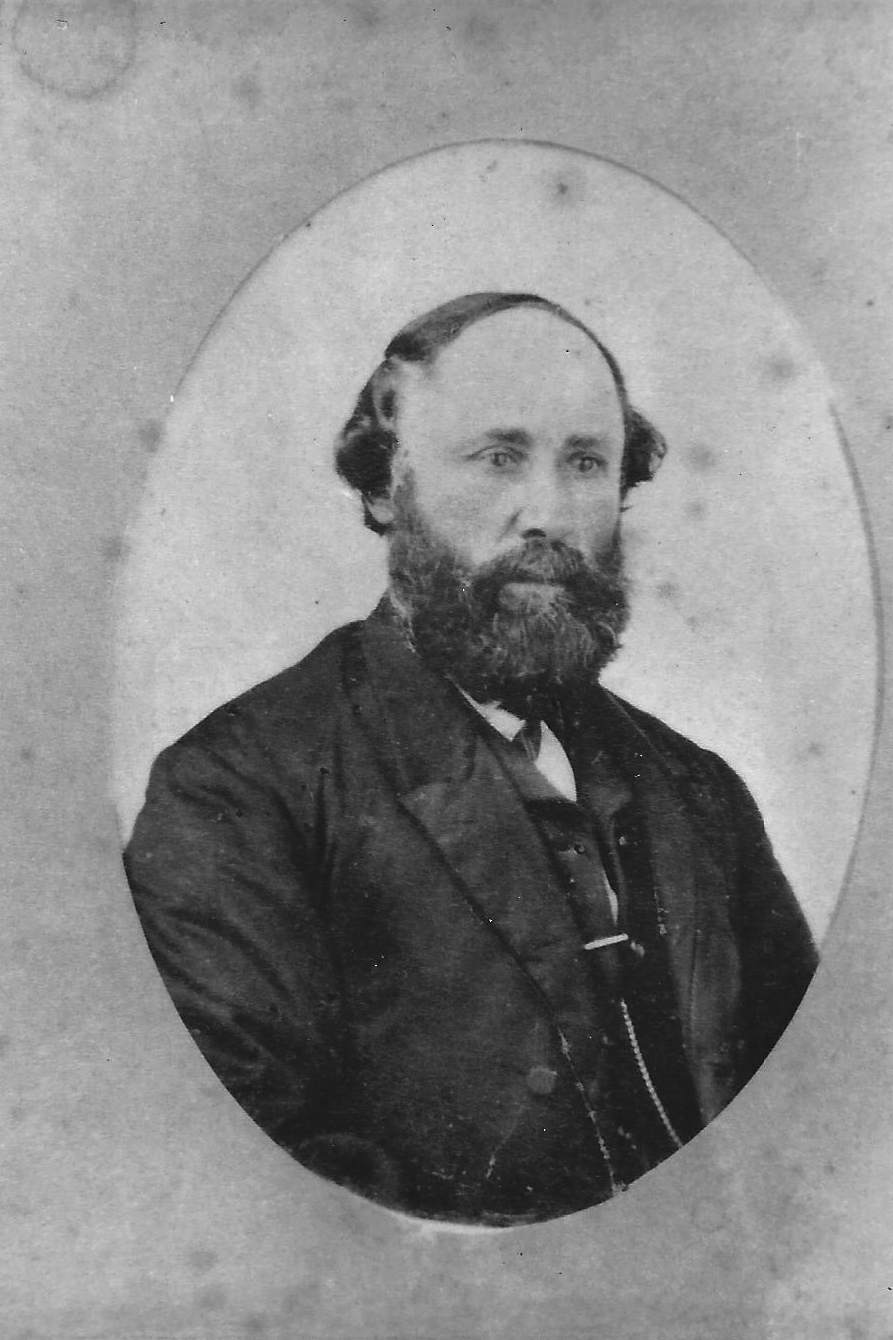

Andrew was born in 1817 at Annabaglish in Kirkcowan, Wigtownshire, Scotland. At the age of 21, in 1838, he sailed by clipper ship to America with his parents and his five siblings, settling in Elgin, Illinois. The ship's list showed Andrew as a “joiner,” a type of woodworker or carpenter. (Mac theorizes that this skill would have made the cabin that Andrew later built in the Washington Territory particularly salable).

After landing in New York, part of the family was left at Croton, New York while Andrew Sr., Alexander, and Andrew Jr. went west to find a place to settle. Andrew Jr. was our 2nd great grandfather, about whom this article is being written. His brother, William wrote a letter back to relatives in Scotland in which he described the family's first experiences in the new land:

“We all thought it best to go to Illinois so they went up the Erie Canal to Buffalo, then up Lake Erie, Lake Saintclair, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan and then they landed at Chicago & went a journey of 40 miles west where they saw a fine Country of Prairie & woodland with not more than 5 or 6 trees on the acre and that will all be needed for fencing and fire wood, as wood is all the fencing is here.” (Meaning no rocks, like back home in Scotland!)

It is reported that a settler named Cyrus, “was familiar with the streets of Elgin, only there were no streets, and one lone log store on the bank of the river and no bridge, and this store was kept by Johnathan Kimball. One of (them) inquired of Kimball, 'Hoo far is it to Elgin?' He replied, 'Gentlemen, you are right in the midst of the city.' The three then, after fording the river, went out west on Highland Ave., only there was no Highland Ave. then and about six miles west they found an early settler who had a claim of 160 acres with a log house on it for which he asked $125. Alexander and Andrew Jr. wanted to look around the country some, but father did not, and as he had the money they closed the bargain. …

“Later in the fall the balance of the family came … William and Andrew (Jr.) took a claim a little northeast … Then Andrew Jr. who had been with William, took a claim across the road … and married Maria Eakin.” (McCornack and Related Families, by Donald A. MacCornack, pgs. 17, 18)

The McCornacks were devout Presbyterians. They came to America seeking a better life. Like the Condons, the McCornacks were already speaking English upon their arrival. Back in Scotland the Scotch language was actively being suppressed in favor of English.

Andrew was pure Scotch. Maria Eakin was Irish. That would not have been an acceptable mixture from the viewpoint of the Scotch Presbyterian New Englanders who routinely turned down Thomas Condon's inquiries about employment there. Interestingly, Thomas Condon's daughter, Ellen, also married a Scotsman, Herbert Fraser McCornack.

Annabaglish

Their ancestors of many generations had lived at Kirkcowan. Annabaglish is a large, old house surrounded by lots of rock fences built by many generations of McCornacks. There is a stone there that has the name inscribed on three sides, with a different spelling on each side. On one side it is McCornack. On another it is McCornick. On the other it is McCormack.

The McCornacks set out on their trip in two covered wagons in April 1853. Their family consisted of five little boys. The eldest was Walter, age eight. The youngest was Herbert, a one-year-old baby, born 10 April 1852, our great grandfather.

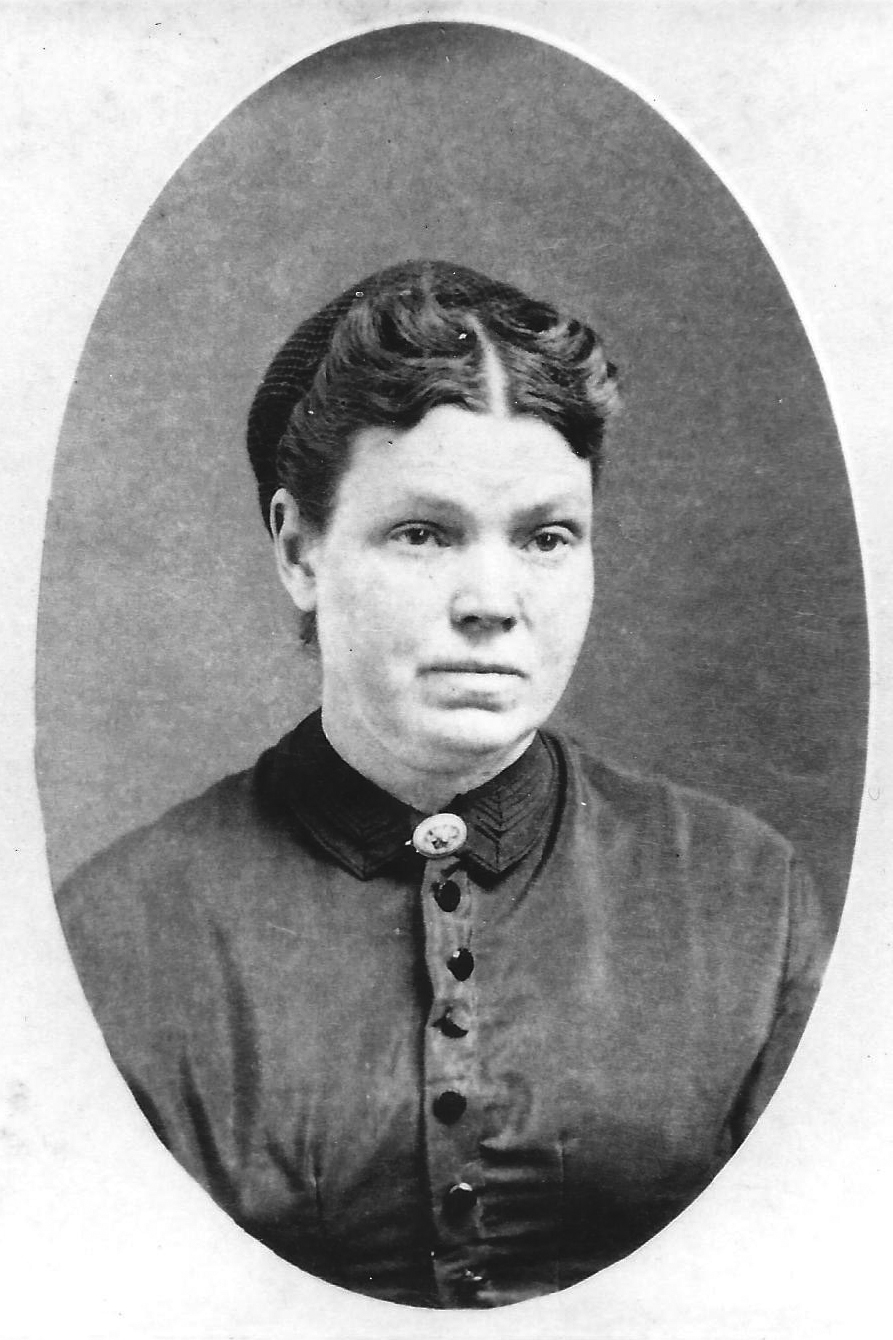

Maria was the daughter of Robert and Margaret Eakin. Maria was leaving her parents and siblings, their home, their friends, and their established and dearly-beloved Presbyterian Church. Andrew secured the blessing of his venerable father, also named Andrew, and they set off on their difficult, 6-month, overland trek to parts unknown.

Why did they do it? What was the call that they felt within? Would they ever see their parents again? How would they keep their small boys healthy? What would they find at the other end? Where would they live? They'd arrive too late in the season to plant crops. How would they subsist?

Andrew never did again see his father, who lived to the age of 98. Maria and Andrew sent letters back to Elgin reporting on their welfare and surroundings, and were followed to Oregon 13 years later by Maria's brother, Stewart Bates Eakin, who brought his family and Maria's parents. Maria's parents, Robert and Margaret Bates Eakin, came over the Oregon Trail in 1866 in a horse-drawn buggy. They were both 70 years old!

Would you take off over wild, uninhabited country with your spouse and children? Would you do it at age 70? Robert and Margaret both lived 10 years after reaching Oregon. Their presence here makes Mac's great grandchildren 9th generation Oregonians.

We can only imagine how difficult the McCornacks' journey was. The welfare of the children was only one of their concerns. There was also the welfare of their animals to worry about. The yokes made big blood blisters on the oxen's necks. The oxen and horses would also become tender-footed if not shod. Even the oxen wore metal shoes. They needed good grass to eat every evening, and lots of water. If their animals faltered, became sick, or died, the pioneers would be in a world of trouble.

The McCornacks also had two milk cows, Nora and Molly. They were much-beloved by the family. Their milk nourished the young boys and kept them healthy. The cream was churned into butter by the bouncing of the wagon. The boys probably did the milking. Those milk cows even took over the job of pulling the wagon late in the trip when the oxen gave out in Wyoming. Later generations of cows were always named Nora and Molly to honor the memory of the two valuable cows that essentially saved the family.

Keeping the wheels of the wagons greased was a big job. Lard was the grease. Indians were a worry. Breathing dust was a constant. Gathering fuel with which to cook a meal where earlier wagon trains had already been was a problem. Earlier trains also consumed the grass. The wagons were most uncomfortable to ride in, so most people walked. Maria probably walked a lot of the way carrying baby Herbert. Was the next eldest, a toddler, able to walk, or did he have to ride cooped up in the wagon?

Unfortunately our grandparents did not keep journals or diaries, nor did they later write about their experiences. A few of their stories were recorded by their descendants, which I will quote later.

To get a feel for their experiences on the trail, and of when they reached their destination, I will quote from a book entitled A Pioneer's Search for an Ideal Home. The author was a pregnant 20-year-old mother of one, Phoebe Goodell Judson, who traversed the Oregon Trail the same year as the McCornacks in a different train. She, too, ended up in the Chehalis/Centralia, Washington area, settling within 10-12 miles of the McCornacks. The two families would probably have met one another at some point.

27,500 people crossed the plains that year, most of them headed for California. The Washington Territory was created that same year, in 1853. The population of white settlers in the Washington Territory that year was just 4,000. Olympia was a muddy village of approximately 25 log cabins, and Seattle was a struggling cluster of cabins even smaller.

Phoebe Judson's small wagon train left Kansas City, Kansas on 1 May 1853. The McCornacks left Elgin, Illinois in April of that year, and probably went to Council Bluffs, Nebraska to be outfitted, and to find a wagon train with which to travel. The McCornacks reached the Chehalis/Centralia area in September, the Judsons in October, after journeys of six months. The McCornack's train, on the north side of the Platt River, where most of the trains traveled, was probably just ahead of the Judsons' train which initially traveled on the south side of the same river.

I will now quote from Phoebe Judson's book to give a feel for what the McCornacks went through on the journey.

“One night, while encamped in a rather exposed place, and all were asleep, with the exception of the guard, we were suddenly aroused from our slumbers by the stampeding of our stock. Oxen, cows and horses came rushing 'pell mell' through the camp, making a terrifying noise which threw us into the wildest consternation. The men rushed after the frightened animals, and fortunately found there were none missing. The Indians, after they had stampeded them, were foiled in their purpose of securing any. They are cowardly, and seldom fight without a decided advantage in position and numbers. After this alarm we were more vigilant in watching for these stealthy miscreants, for pitiable indeed would have been our plight had they succeeded in capturing our teams. …

“The water (was) very roily. We were compelled to allow it to settle before using. We found water and grass in abundance, but wood was very scarce, except in places near the margin of the river. The river bottom land was so soft and muddy that we were in constant fear of losing our teams, and for many days the cool north wind made traveling very unpleasant. …

“How much we missed our camp fires at night in these cheerless places, not only for culinary purposes, but to brighten the dreariness of the way. But my sympathies were more with our men, who were wading through the mud and sloughs, day after day, driving their teams. There seemed but little rest for them night or day …

“Buffaloes were often seen at a distance, in droves, but we had no time to capture them. One day we were so fortunate as to come across two that had been slain by the train ahead of us, and as they had carried away but a small portion, we helped ourselves and left an abundant supply for the next train. Our buffalo steak compared favorably with beef, and better relished on account of it being the first fresh meat we had tasted since we began our journey. …

“For many days we traveled in sight of long emigrant trains on the opposite side of the river, and we judged that the heaviest portion of the emigration was on the north side of the Platte, which made it all the better for our stock...They were the trains that had fitted out at Council Bluffs, and I presume were making as good time as ourselves. (The McCornacks were in one of those).

“On reaching the south fork of the Platte we found that the river was rising caused by the melting snows from the Rocky Mountains, and was one and a half miles wide. Many of the trains went farther up the river before crossing, but our captain concluded it was best to cross here. We were obliged to double team, making eight yoke of oxen to each wagon. The beds of the wagons were raised a number of inches by putting blocks under them. When all was in readiness we plunged into the river, taking a diagonal course. It required three quarters of an hour to reach the opposite shore. After starting in we never halted a moment, for fear of sinking in the quicksand, of which there was much danger. We found the river so deep in places that, although our wagon box was propped nearly to the top of the stakes, the water rushed through it like a mill race, soaking the bottom of my skirts and deluging our goods. The necessity of doubling the teams for each wagon required three fordings, consequently by the time the last wagon was brought across the whole day was consumed. Thankful were we when night found us all safely encamped on the west side of the Platte, where we remained a day in order to dry our goods.

“One of the dreaded obstacles on the journey had been successfully overcome, and we proceeded on our way up the valley of the North Platte with lighter hearts. We found the water, if possible, more roily than that of the South Platte.

“Most melancholy indeed was the scene revealed as we journeyed through this valley—the road was lined with a succession of graves. These lonely resting places were marked with rude head boards, on which were inscribed their names, and 'Died of cholera, 1852.'

“Many of these graves bore the appearance of being hastily made. Occasionally we passed one marked 'killed by lightning,' which was not surprising to us after having witnessed one of the most terrific thunder storms it had been our fortune to experience. This storm broke upon us after we had retired for the night. One after another, terrific peals of thunder rending the heavens in quick succession, roaring, rolling and crashing around, above and below, accompanied by blinding flashes of lightning, illuminating our wagons with the brightness of noonday, while the rain came beating down upon our wagon covers in great sheets. It was simply awful. …

“Our guard, being insufficiently protected, fled to the camp. The captain and his brother, having gum coats and everything necessary for such an emergency, sallied forth, and by indefatigable efforts succeeded in keeping the frightened animals from stampeding. …

“In the morning we found there was not a head of our stock missing, while other trains that were camped near us had allowed theirs to be scattered for miles away. Our bedding and clothing were as wet as water could make them, but the sun came out brightly in the morning, and we were again compelled to lay over a day to dry them. …

“In many places along the route we found the water so strongly impregnated with an alkaline substance as to make it poisonous for both man and beast.” (Phoebe Judson, pgs. 28-33).

“Coming down again onto the river bottom, we passed a row of twenty graves. By the inscriptions on the rough head boards we learned that they died within a few days of each other of cholera. …

“The next noted land mark to which we came was Chimney Rock, the tall chimney having been in view, and seemingly quite near, for several days, the peculiarity of the atmosphere causing distances to be quite deceptive. We camped within two miles of it, giving a number of our party the pleasure of paying a moonlight visit to this curious freak of nature, with its chimney-like shaft rising to a height of one hundred feet.” (Ibid, pgs. 35-36).

“The next river that we forded was the Laramie. This river was narrow, but so deep that the water covered the backs of the oxen. When across, we found ourselves at Fort Laramie, another 'landmark' on our journey, where we remained two days and dried our goods. …

“After leaving Fort Laramie we began the ascent of the Black Hills. Our route over these hills was a perpetual succession of ups and downs, and the aspect of the country drearily barren. The soil was of a reddish clay, intermixed with fine, sharp stones. These stones cruelly crippled the feet of the oxen. Old Tom, one of our heavy wheel oxen became quite lame for a time. The poor fellow was obliged to limp along, as it would not do to lay over among these barren hills.

“Laramie Peak towered above the hills, and there patches of snow were visible.

“We reached La Bonta Creek on Saturday, a little before sundown, and made our encampment on its banks, among the cottonwood trees, one of the most charming spots of the whole route, where we found good water, grass and wood—which was greatly appreciated.

“The Sabbath dawned most serenely upon us, a bright, lovely morning, the twenty-sixth of June. I am certain of the date, for the day was made memorable to me by the birth of a son.” (Ibid, pgs. 37-39).

“The captain decreed that our wagon should lead the train (although it was not our turn), saying if 'our wagon was obliged to halt the rest would also.'

“It proved the roughest day's journey through the Black Hills. The wind blew a perfect gale, and while going down some of the rough sidling hills it seemed that the wagon would capsize.” ...

(Ibid, pgs.40-41).

“The fifth of July we reached another point of interest—the Devil's Gate, where the Sweetwater had cut its way through a spur of the mountain, rushing through a rocky gorge with perpendicular walls from three to four hundred feet high. …

Devil's Gate

“Passing over the ridge through which the river had cut its way, we again came into the valley of the Sweetwater, and had our first view of the Wind River mountains … We had many hills to pass over that bordered the river, which we forded twice, and found the water deep and cold. Ice formed in the camps, and banks of snow lay by the roadside, making the air so chilly that we were obliged to wear heavy wraps to keep from shivering. …

“At noon, on the twelfth of July, we reached the highest altitude of the Rocky mountains. The ascent had been so gradual that it was difficult to distinguish the highest point. From the beginning of our journey we had been wearily toiling on an upward grade, over vast prairies, up high hills, mounting higher and higher—not realizing the elevation to which we had attained, and now had nearly reached the region of the clouds, without being aware of the fact.”

“From the summit of the mountains to Green River our road led us through the most barren country of our experience, causing us much anxiety for our cattle. The nights were frosty, and the cold winds through the day made traveling very disagreeable. As we traveled along this barren ridge, Green river came frequently into view, flowing swiftly through the grassy plains. Cottonwoods waved their green branches by its silvery current. Our anticipation for the comfort of our cattle ran high. Already we could see them luxuriating on the succulent grass and slaking their thirst with the crystal waters.

“Alas! for the poor cattle, when we reached the coveted spot, to our deep distress, the grassy plain proved to be but thorny cactus and bitter greasewood. …

“The river at this point was about three hundred feet wide and the swimming of the stock was only accomplished after many ineffectual efforts to drive the reluctant animals into the cold, rapid stream.

“The great anxiety experienced by the emigrants at these river crossings can hardly be realized. The lives of our men were in constant danger, as they forded these perilous streams on horseback—swimming the stock.” (Ibid 45-47).

“As we descended into the little valley a band of mounted Indians appeared … careening wildly across the valley toward our train—hair and blankets streaming in the wind. … They galloped furiously around and around the train, endeavoring to peer into the wagons. … We did not understand the cause of their threatening manifestations, (but) … the Indians left us to bestow their unwelcome attentions upon other trains.

“We were not long left in doubt as to the cause of these exciting maneuvers. Two men appeared, before we were fairly settled in camp, fleeing for their lives, seeking protection among us … These men, who were on their way from Oregon to the states, got into trouble with the Indians and had killed one of the savages, as they claimed, in self defense. …

“We greatly feared an outbreak from the Indians before morning, and all of the trains in that vicinity prepared for a battle, by coming together and forming a large circle with their wagons. (Were the McCornacks in the circle, I wonder?) …

“The Crow Indians followed us for a number of days, bent on revenge, but feared to make an attack unless they had the advantage of an ambuscade. … When safely out of the Crow Indian country, the two men emerged from their hiding places, where they had been so effectually concealed that the avengers of blood failed to find them, although they had peered into the wagons of every train. They returned to Oregon, as they were afraid to continue their proposed journey to the states, and no doubt some innocent party paid the penalty for the death of this Indian.” (Ibid, pgs. 49-51). …

“We crossed a few more small streams, usually finding good water and grass for our stock, but frequently a serious drawback to our comfort was a dearth of wood. Green willow, the size of a pipe stem, being the only substitute. Over this sizzling, smoky apology for a blaze we managed to heat water for our tea. I must say I preferred the willow to buffalo chips, which many emigrants used for fuel.

“Fort Hall now lay before us in the near distance. To this point, located in Eastern Oregon, which we thought lay near the end of our journey, our longing eyes continually turned.

“Arriving at Fort Hall, weary and worn with our long journey of more than a thousand miles, after the slow, plodding oxen, our hearts sank with dismay when we learned that eight hundred miles still stretched their toilsome lengths between us and the coveted goal of our ambition. Had we known of the desolation and barrenness of the route that lay before us, I fear we would have been tempted to give up in despair, for it proved by far the roughest and most trying part of our journey. …

“(We) made our first encampment on Snake river, a name ominous of treachery and tribulations.

We were immediately besieged by great clouds of mosquitoes, which annoyed us most unmercifully. By tying down our wagon covers as closely as possible and burning sugar to smoke them out, we managed to get a little sleep; and in the morning left this camp without one regret, like nearly all others from this one to the end of our journey. …

“Following down this desolate valley, where scarcely a vestige of vegetable life appeared, we crossed several streams where it was so rough with rocks that it seemed as though our wagons would be broken to pieces.

“On reaching Raft creek we filled our water kegs and carried water with us, as our next encampment would be a dry one.

“For several days we traveled over a country that was too dismal for description. The whole face of the country was stamped with sterility. Nothing under the brassy heavens presented itself to the eye but the gray sage brush and the hot yellow sand and dust. Our men traveled by the side of their teams, with the burning rays of the sun pouring down upon them—the dust flying in such clouds that often one sitting in the wagon could see neither team nor the men who drove them. Camping at night where water and grass were deficient both in quantity and quality. There seemed but little life in anything but the rattlesnakes and the Snake Indians.

“The name was no misnomer, for these Indians were as treacherous, and their poisoned arrows as venomous as the reptiles whose cognomen they bore. Concealing themselves behind rocks, or in holes dug in the ground for that purpose, from which they assailed the emigrants and their stock with poisoned arrows, and were more to be feared than any tribe we had encountered.” (Ibid pgs. 52-54). …

“On a stretch of more than two hundred miles the country was nothing more than an arid waste; vegetation was so badly parched that our cattle could find but little subsistence. Tom and Jerry, our wheel oxen, became so thin and weak that they began to stagger in the yoke. In my great pity for the suffering creatures, whenever it was possible I walked ahead of the train and gathered into my apron every spear of grass I could find and fed them as we traveled. This, I doubt not, helped to save their lives. When the close of the day's journey brought us good water and grass both, we were rejoiced; and when so fortunate as to find good water, grass and wood, all three, we felt ourselves blessed indeed. No one can fully appreciate these common blessings of life until they have been deprived of them in a hot desert country. The hot sunshine and dust, with the constant disagreeable odor of the ever abundant sage, or greasewood … took away my appetite, and for a time I became so ill that my life hung in a balance. … All of the little delicacies we brought with us from home were gone, and we had nothing left but flour, bacon, beans, sugar and tea. And, like the children of Israel, my soul loathed this food and I longed for something fresh.” (Ibid, pgs. 55-56).

“When we reached Fort Boise we found that our wagons must be ferried over the Snake river at the exorbitant price of eight dollars per wagon. … Having replenished our stock of provisions at the fort, we were enabled to provide a better bill of fare than usual; and as this was the last crossing of this dreaded river we were all in the best of spirits, hoping soon to be out of the Snake river region.” (Ibid, pg. 62).

“After leaving Malheur river our road led us over alkaline deserts, up and down high hills, occasionally coming to a stagnant pool whose waters, like those of Marah, 'were bitter to the taste.'

“We were two days traveling up Burnt river, continually enveloped in clouds of suffocating dust.” (Ibid, pg. 64).

That one sentence is all that Phoebe Judson said about the Burnt River canyon. I need to add more, since it is part of our own neighborhood. There was no road, and there were no bridges. Because of the steep hills that came right down to the river, passage was difficult. It was necessary for the trains to cross the river eight times, and to precariously drive sideways along steep hills at some points. The wagons would have tipped over had not men gathered on the upper sides of the wagons and held on to keep them from rolling down the hill.

The McCornack's train crossed the east side of Baker Valley in August. The valley was swampy, and uncrossable. The mountains were beautiful, but also formidable, and a worrisome sight. They were the first mountains on the whole trip that the pioneers had seen close up. They hadn't even seen the Rocky Mountains because of the gradual ascent that they made. Many pioneers cried when they saw the Blue Mountains, knowing that it would be necessary to cross them.

As the McCornacks passed through Powder River Valley, they never once imagined that their descendants would one day live in that valley, and that their descendants would consider it an Eden.

The Oregon Trail exited Baker Valley a few hundred feet west from where Highway 80 currently climbs the hill. The wagons went straight up the steep hill, and up on top, crossed to the other side of the present-day freeway where they climbed more hills. Passage down Ladd Canyon was impossible. At the top of the last hill, before descending into the Grand Ronde Valley, the occupants of each wagon cut down a pine tree, lopped off the limbs leaving foot-long stubs, and tied the tree to the back of the wagon. The tree served as an anchor as it dug into the ground, keeping the wagon from overrunning the oxen as they made their descent. As a small boy, James thinks that he can remember a big pile of old trees at the bottom of the hill where the wagons jettisoned their anchors.

Riding in the wagons was not comfortable. Walking was preferable, especially while crossing the Blue Mountains west of what is now La Grande. The first wagon train blazed what would become the Oregon Trail. That was the Applegate Train in 1843. An Indian guide showed them the way. Teams of men went before the wagons chopping down trees to make a narrow roadway. The stumps remained. The wagon wheels had to climb the stumps, and the wagons would then come down with a bone-jarring whump. Ten years later, when the McCornacks came through, the stumps were likely still there. The only people aboard the wagons were probably the drivers. The driver of the McCornack wagon was often 8-year-old Walter.

Now back to Phoebe Judson:

“Making one dry camp, we descended into Powder river valley, and encamped for the Sabbath, where we were made happy by a pure stream of running water. Travelers on the Sahara could not have appreciated it more than these dusty, dirty emigrants, after traveling over high, barren hills, their imaginations haunted by visions of babbling brooks and bubbling springs. …

“Crossing Powder river and several other streams, we ascended a mountain. On reaching the summit, our captain called a halt, that we might more fully view the magnificence of the grand Powder river valley, which lay unrolled beneath us. The beauty of this enchanting scene filled our souls with delight—surrounded on all sides except the west by blue mountains, covered with evergreen timber.

“We rolled down the mountain into this picturesque valley. Crossing to the west side, we encamped near where the city of La Grande is now located. Many Indians were galloping over the prairies, sitting as straight as so many cobs, on the little ponies which run wild over the plains...” (Ibid, pgs. 64-65).

“We crossed the Grande Ronde river and soon after bid good-bye to the beautiful pine forests and came out upon the summit of a bald mountain that overlooked the great Columbia river valley … In the rarified atmosphere of these upper regions this inspiring scene seemed but a short distance away … The one sentiment animating our souls was to reach Puget Sound as speedily as possible; and we fondly hoped that the remainder of our journey would not be as full of difficulties as that which lay behind.

“Oh, vain, delusive hope! For we found the more sublime the scenery the more difficult became our progress. The descent from the mountain was steep and rocky. We made our encampment on the bank of the Umatilla, where we found good grass for our cattle.

“This wild, picturesque valley was filled with Indians who were trading with the emigrants. We bought fresh beef from them at twenty-five cents per pound, and potatoes (no larger than walnuts) at one dollar a peck; but they were 'potatoes,' and we ate our supper and breakfast with more relish than any meal since we left home.

“After crossing the Umatilla river our road led us over a desperate country—up and down steep hills and through rocky canyons, in which grew nothing but sage brush and thorny cactus, many times traveling all day under a scorching sun, without water, our eyes, ears, nose and mouth filled with dust. One night in particular, I shall never forget. We were obliged to make a day camp—the wind was blowing a hurricane so that we were unable to build even a sage brush fire. Locking the wheels of the wagons to keep the wind from running them down a chasm, we went thirsty, hungry and dusty to bed. …

“At John Day's river we stopped only long enough to fill our water kegs and then drove on up the canyon to a grassy plain and encamped for the night. Indians often swarmed around the wagon while in camp, begging for food. …

“Mt. Hood had been in view for several days, the transparent atmosphere, annihilating space, made it appear but a short distance away. We traveled towards it slowly and patiently, day after day, never seeming to diminish the distance between us, when finally, one Sunday morning, while searching for a good resting place for our stock, we suddenly came onto the banks of the great Columbia. At last, at last, at long last, we were surely near the end of our journey. … There was nothing attractive in the scene, not a tree, spear of grass, or vegetation of any kind to be seen, so we drove on down the river for a few miles and came to the Des Chutes river. Its bed was filled with great boulders, against which the rapid waters dashed and foamed as it sped on its way into the Columbia, making a hazardous fording place. …

“We were obliged to continue our journey to find food for our stock, and after climbing several high hills came to a beautiful grassy valley, through which meandered a clear rippling stream called Fifteen Mile creek, and thankfully made our encampment for the night.

“The next day our road led over high hills that bordered the Columbia, and, after descending its banks, we came to a little trading post called The Dalles, which at that time was composed of a few zinc cabins and tents occupied by Frenchmen ...” (Ibid, pgs. 68-71).

I apologize for quoting all of these pages from Phoebe Judson's book, but she did an excellent job of relating what must have been the exact experiences that our McCornack family had as they came on the Oregon Trail at that exact same time. I theorize that the McCornacks were just several days ahead of the Judsons, and were heading for the same place. Since our grandparents didn't write their story, Phoebe Judson's will have to serve as our history. I consider it very accurate.

At The Dalles, however, the McCornacks did things a little differently than did the Judsons. The Oregon Trail essentially ended at The Dalles, because the narrowness of the canyon, and the Cascade Falls, made further travel by wagon impossible. Here Andrew McCornack put Maria, the four younger boys, and their gear in the care of two Indians with a bateau, an Indian boat. He and Walter, the 8-year-old, would drive the livestock overland, and the family would reunite at Cowlitz Landing up the Cowlitz River.

Separating the family like that in an unfamiliar land, with the understanding that they'd meet again somewhere in the wilderness, seems an awfully brave thing to do. But what actually took place was that as Maria floated down the Columbia, and was being paddled up the Cowlitz, Andrew was actually not far away, following the banks of the same rivers. He and Walter drove the stock down the south side of the Columbia to Cascade Locks, and swam them across to the north side below the Cascades. They followed that bank of the Columbia until they hit the Cowlitz River, and then followed that river northward until they came to the meeting place.

Phoebe Judson also paddled up the Cowlitz with the Indians. Here is her account:

"We began the ascent of the Cowlitz River in an Indian canoe propelled by Indian muscle, making about the same speed against the current as did our oxen when pulling up a steep mountain. There were many portages, where jams of logs obstructed the river. Frequently the water was so shallow that the Indians pushed the canoe along more rapidly than they paddled through the deep water. For a time the novelty of the scene was quite interesting, but, as there was a lack of variation, it soon became monotonous—only varied by the mild excitement of the occasional salmon leaping from the water.

"Sitting in one position all day, in the bottom of a canoe, we found very wearisome.” (Pgs. 78-79).

I will now insert an anecdote about Maria's river trip written by Eugene R. McCornack, the son of Walter, the boy who drove the livestock along the shore:

“The extreme difficulty of the overland trip made it necessary for the family to separate, Grandfather and Walter taking the … livestock overland and Grandmother with her four little folks going by water, down the Columbia and up the Cowlitz to meet the overland party at some designated spot in the wilderness of these northern woods. A large Indian bateau carried Grandmother and the children. There huddled in the bottom of the bateau with her four little boys about her, with their destiny in the hands of savage and not altogether prepossessing Indian boatmen she faced the future. Here again a faith in the goodness of God must have been a sustaining factor.

“Not a word could be spoken which these savages understood. Grandmother made a camp by the riverbank when the Indians brought the boat to shore. She arose with them as the tide or the winds or the moon prompted them to travel. Those must have been trying days but years later Grandmother in relating the story to her grandson laughed away the hazards of the journey and told how the boatmen, faithful to their trust, had delivered them at the appointed spot on the riverbank where the family was reunited. With a little embarrassment she laughingly told of one amusing incident. With the health and comfort of her little folks in mind she had on leaving the Illinois home insisted on bringing along a little child's bedroom vessel, a thing almost unheard of on the frontier of that day. The first morning beside the river she woke up to find the Indian boatmen using it in preparing their breakfast. By signs she sought to protest its use for this purpose attempting to tell them it was an improper use they were putting it to. The red men in turn assured her that they were not harming it in any way and that it was a great convenience in preparing their meals. It remained in the Indians' possession throughout the trip and was returned to her unharmed with a show of pride on the part of the simple natives, as of a trust fulfilled.”

McCornack homestead

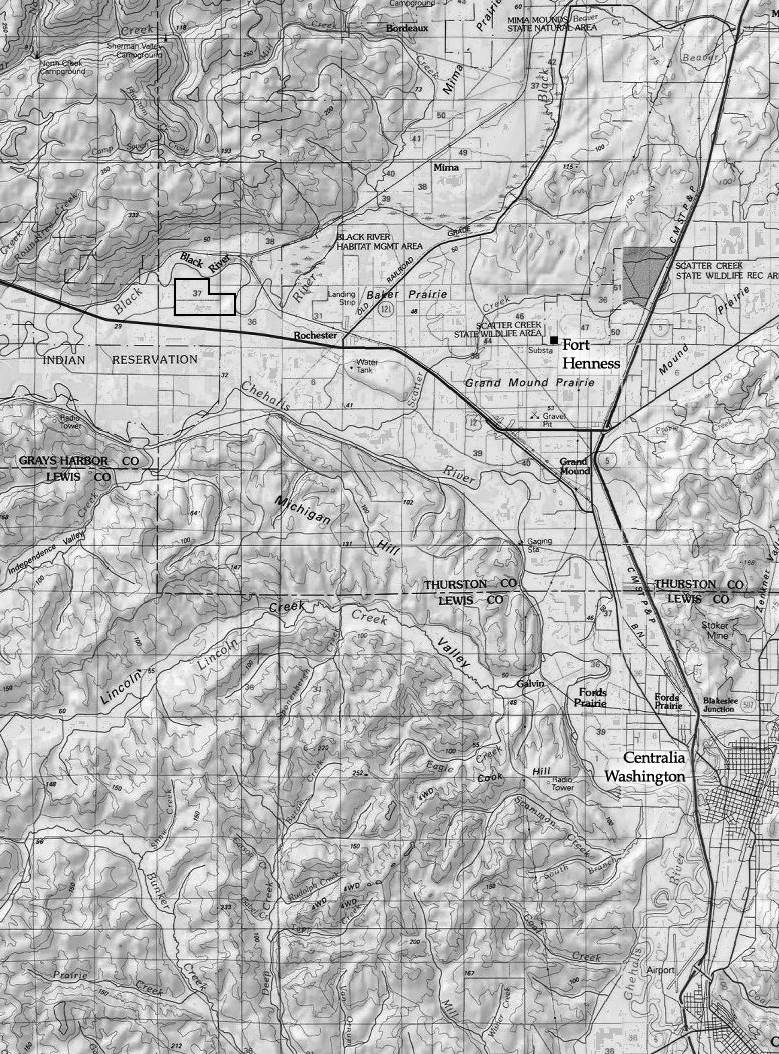

Andrew led his family to an area called Grand Mound Prairie just north of what is now Centralia, Washington. He went a little west and selected 320 acres as their homestead. The Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 provided that a married couple could claim 320 acres free of charge, provided that they live on the land and cultivate it for four years. The act stipulated that after 1854 the same land would cost $1.25 per acre.

Mac's grandfather, Elwin A. McCornack did an excellent job writing about several things which these intrepid pioneers experienced. I will now switch to quoting from him.

“Grandfather lead his family to the Puget Sound country—now Washington state—and settled in a wild and worthless country near Fort Nesqually. His locating there was a mistake and was probably due to the fact that a Presbyterian church and school had been established there.

“A cabin was built, land broken and pioneer life began. Indians were everywhere but usually friendly and the growing boys learned much of their ways—how to take salmon with ingenious native spears; how to hunt the game which abounded in the woods and to speak fluently the picturesque Indian jargon. Wild animals preyed on the stock and had to be hunted and snared. Wild cattle and hogs roamed the woods and sometimes put the boys up the trees. Their stories of escape are rich in adventure. On one occasion when the five boys were herding cattle on the far side of the river a panther which had been preying on the cows began screaming nearby. Walter, realizing that the cattle would stampede for home leaving the boys on the wrong side of the river with the beast, gave orders for each boy to get a cow by the tail. The stampede started, the boys hanging on desperately through brush and water until all reached safety on the other shore.

“Indians were sometimes troublesome. Once when the parents were away an Indian insisted on a drink of water. Walter stationed himself with a musket and told Ed to offer him a dipper of water through the door. As the door opened a bit the Indian stuck his foot in the opening and forced his head in. Walter's quick, 'Klatawa hyac,' and the leveled rifle were too much for the red man's nerves. He had seen enough of the inside of the white man's house.

“It is related that two especially large Indians became troublesome, strutting back and forth in front of Grandfather challenging him to fight. They refused to go away and became more insolent. Grandfather, a man of unusual strength, suddenly seized each Indian by the scalp-lock and drove their heads together with such force as to thoroughly take the fight out of them.

“This, however, was a poor farming country and it was decided to make a move. Everything was again loaded into the wagons, this time with two little girls, Helen and Janet, and the trek with flocks and herds made into the Willamette Valley. Here another mistake was made as again a start was made back in the hills, this time the Camp Creek Valley, where a school and church had been established. It proved, however, that feed was not plentiful and many of the stock died of larkspur. A move was imperative and this time a location was selected on open valley land west of Eugene, and again all set to work. In a very few years the family owned seven hundred acres of good farm land and were successfully engaged in growing grain and raising livestock.

“It was here the family grew up—seven boys and five girls—working at home on the farm and going to school. It was from here they scattered up and down the Pacific coast, everywhere taking a substantial and leading part in the civic and industrial life of the communities in which they lived. They played a full part in the building of the Great West.

“Grandfather was a believer in good stock and a great lover of horses. When he came from Illinois he brought with him a black mare of Morgan breeding, by the name of Kate. Horses were dear in those days and Kate was all the family could afford, but she had been selected with a fine eye for quality. She lived many years bearing many foals, finally being blind from falling in a well but always the object of pride and affection. In later years the family was noted for its good horses, and the men would show with pride those which were descendants of old Kate. The family also held in affection the names of two of the cows that, after the loss of the oxen in Wyoming, pulled their wagon across the plains and at the same time supplied the little folks with the life sustaining milk. These names, Nora and Molly, were for years given to favorite domestic animals.

“While driving a spirited team in 1872 Grandfather was thrown from the wagon and killed. Good horseman that he was, he would want me to add that it was not inability on his part to handle the team which caused the accident, but the dropping of the wagon tongue and the over-turning of the wagon. He had, however, lived a life of broad usefulness and was much respected. I have been told by old timers that the train of sixty carriages and wagons which followed him to burial set a precedent in that day. He, with Walter and Ed, enlisted in the first Oregon regiment during the Civil War and while Ed saw hard service against the Indians, the units to which the others were attached were held in reserve to protect the settlements.

“He served in the Oregon Legislature in 1865-67 and in an effort to reduce the evils of the liquor business of that day, introduced and secured the passage of a bill placing a license on saloons. Oddly enough the writer years later, while serving as chairman of the committee on alcoholic traffic in the Oregon Senate, found himself drafting and passing liquor control legislation following the repeal of the eighteenth amendment. Family tradition has it that Grandfather saved enough from his meager state pay at one session to buy Grandmother a washing machine—a luxury almost unheard of in those days. This, the writer can say, is more than he was at any time able to do during his term of legislative service.

“I cannot go on without reference to Grandmother. Grandfather I never knew, but of all of my childhood recollections, none are so dear to me as the memory of this little woman. Though firm in matters of right and wrong she had a gentleness and understanding that drew small boys to her irresistibly. This seems to be more remarkable when we realize that much of her life had been spent in a rough and sometimes bitter struggle in a wild country. Her interest in young people was tremendous and their well-being and education were dear to her. A great reader of good books, she never ceased to educate her own mind. Some of her most successful sons have credited her with an inheritance which made it possible for them to accomplish the things they did.”

Now I must pause and go back to the Oregon Trail so as to insert this story written by our Grandfather's brother, Condon C. McCornack:

Grandfather's Prayer

“While crossing the plains somewhere between South Pass and Green River, Grandfather's wagon train was persuaded to take a short cut. After some days they became lost and found they were wandering aimlessly among the hills and could not find the way out. They went into a dry camp while Grandfather climbed over several intervening ridges to a high hill, or side of a mountain from which he was able to get a good view of the country and plainly see the parked train and the way in which they should go. However, while returning to the train through the hills, a fog came down and he became confused in his directions and found he was lost, with no idea where the train was. He became greatly perturbed over the fate of the train, as he was the only one who could save them from death by thirst. He thereupon got down on his knees by a large rock and prayed that God would help him find the train and keep the many innocent souls there from death. Upon arising from prayer, although the country was still enshrouded in fog, he looked carefully in every direction and said to himself: "The train is over there." He at once set out in that direction and after a half hour saw the train in the valley directly ahead of him. After a short prayer with family and friends to return thanks to God for their deliverance, they hooked up and proceeded in the way he had chosen, without further difficulty.

“That is the story that was first told me by Grandmother, and years later by Aunt Mary. It illustrates something of the times and the man and it is immaterial whether it was, as his immediate family devoutly believed, a direct intervention of God in an answer to prayer; or as the modern materialist or psychologist would say, a simple natural sequence in that Grandfather's rest and short distraction from worry cleared his mind and allowed his normal judgment to become uppermost; or as some believe, it was the working out of one of the laws of nature all of which are the methods by which Divine action is exercised rather than by direct intervention.”

And now another story, this one by our grandfather, Elwin A. McCornack, written about his father, Herbert Fraser McCornack, our great grandfather. Herbert was the baby on the wagon train as they crossed the plains.

The Little Boy and his Buckskin String

“Of the five young boys in the McCornack family who trailed west in the covered wagons in the early eighteen-fifties Herbert was the youngest, just a year old as the family left their home state of Illinois. Grandmother thought that it was because he was confined to the wagon at a time when most children are learning to walk, later day specialists say it was an attack of polio that brought on the impairment, but when the little lad was two and three years old he had all but lost the use of one leg and of course had much difficulty in walking at all.

“Grandfather and Grandmother were very busy people struggling to keep the family fed and shelter provided. The smaller children were left largely to the care of the older boys, and these older boys were very, very active youngsters. One day they went to the river for fish. Using a native Indian spear they succeeded in spearing and landing a salmon so large that not one of them could lift it. Walter, improvising a harness from scraps of buckskin, hitched a four horse team on to it, and with little Herbert running along behind as driver, they brought their big catch up to the house.

“Another day, with their dog Coley, they foraged for blackberries. They disturbed a drove of wild hogs sleeping in the bushes, and the enraged hogs rushed the boys with such fury that they were glad to find safety on a big log drift beside the river while Coley fought the enraged hogs. In the struggle which ensued, Coley was able to get a strangle hold on a large boar; and notwithstanding the frantic struggles and squealing of the boar, Coley hung on until the hogs fled in panic into the woods dragging the little dog with them. It was only then that the boys ventured down from the log pile and pursued the trail left by Coley and the hogs. After following it some distance they came upon the body of the boar where the little dog, still hanging to its throat, had killed it. The boys had to carry Coley home as he had received a broken leg in the fracas; but the little dog was acclaimed a hero, and commended for his service to the family.

“Still another day the boys ran into a herd of wild cattle, great long horned brutes, who attacked on sight, and precipitated some amateur bull fighting by Walter and Ed while Will and Gene found trees which they and little Herbert could climb. Again little Coley was in the forefront of the battle, and with the help of the older boys was able to drive the cattle away.

“I fear I have wandered away from the subject of this narrative to some extent, but I bring in these incidents to illustrate the kind of life this little boy lived and how important it was that he be able to travel. Keeping up with his brothers with one dragging leg was the next thing to impossible. This was his problem. Determination and ingenuity became the answer. He found that by attaching a broad soft buckskin strap to the large toe on the impaired leg he could run by jerking the lagging leg ahead to complete each step. No doubt it was difficult to do at first, but he soon learned to hitchskip along at a pace which permitted him to keep up with his brothers. With use and activation the lagging leg improved, and within a year or so he had overcome all impairment and grew into a strong, able man. However, as a reminder of what he had been through as a boy, one leg always remained a bit shorter than the other and he walked with a slight limp.

“I have always thought of this as an interesting story of pioneer times and of one little boy's determined fight against adversity. The story has more recently taken on new interest when I read an article on the most advanced methods of treating certain types of paralysis of the lower limbs, and studied a brochure featuring a recent scientific mechanism invented by two eminent specialists which may be attached to an immobilized member to assist in its reactivation. A careful study of the new device disclosed that it had nothing that the small boy's hand-operated buckskin string did not have. I call it an outstanding instance of native ingenuity and fortitude of a little boy raised in the wilderness. It is also an interesting fact that Uncle Dock, as his young nephews all called him, went on himself to become a skilled physician and surgeon.”

Grandfather Elwin McCornack called Andrew's choice of this place near what is now Centralia, Washington a “mistake.” In other ways it was fortuitous, for here they were able to put in a winter's food supply (which they must have done) by harvesting and drying salmon even though they arrived late in the season. Just imagine all of the work that would have been required for them to do, almost all at the same time. A cabin had to be built. It had to have a working fireplace. Food had to be laid in for the winter. Ground had to be cleared for planting in the spring. Providing firewood for heating and cooking was a daily chore.

How we wish that someone in the party had kept a journal. We have many questions about their journey, their accommodations, and their hardships. Thomas Condon kept a log on their voyage around Cape Horn in which he daily recorded the miles they'd sailed as reported by the captain of the ship. Three individuals in the 1866 Eakin party kept diaries which enable us to follow their progress over the Oregon Trail. Those diaries were brought together in a little book published under the title, A Long and Wearisome Journey. We are also grateful for Phoebe Judson's book, for her history is ours.

The lesson to be learned here is that our lives need to be recorded. We tend to think that we're just ordinary, uninteresting people, but just see how fascinated we are with the history of these ancestors. How we long to know the details of their lives and of their experiences. Our descendants a hundred years from now will be just as hungry to know how we lived our lives, and how we endured our hardships, and how we viewed the political storms that currently envelop our world.

The McCornacks and Phoebe Judson settled at Grand Mound, “an area of many square miles, a place of great natural beauty. A lone, bare mound, one hundred feet in height, rose in the center of the southwestern part,” Phoebe Judson reported. She said, “This prairie was abundantly covered with wild bunch grass, and was surrounded by stately evergreens. Mt. Rainier, with her white hood, in the background, overlooking all.

“Here we located our claim of three hundred and twenty acres … Had the soil been more productive, it would have been a profitable investment … Mr. Judson began at once to fall the fir trees and hew them to build our habitation, the dimensions of which were sixteen by eighteen, surmounted by a shake roof, and the floors of the style called puncheon. The shakes, puncheon, doors, bedstead, table and stools were made from lumber split from a green cedar tree.

“The fireplace he built of blue clay that was hauled from some distance, mixed with sand, and then pounded into a frame model. When it became dry, he burned the frame, which left the walls standing solid.

“An old gun barrel, the ends embedded in either jamb, answered for a crane to attach the hooks to hang the pots and kettles. The chimney, built of sticks and mortar, ran up on the outside of the house.

“When the crevices were chinked with moss we moved into our rudely built cabin, with scarcely an article to make it look attractive or homelike. Holes were sawed through the logs for windows, and over them I tacked white muslin to keep out the cold and let in the light. They were quite small, I remember, for while at the spring for a pail of water, Annie, the little mischief, (3-years-old) pulled the 'latch string' through and could not replace it. As she and the baby were both crying, there seemed no other alternative for me but to go down the stick chimney, or through one of the small windows. I chose the latter, as I was still quite slender, and barely managed to crawl through.

“Mr. Judson put up a few three-cornered shelves in the chimney corner, on which I arranged my china and glass ware, which consisted of three stone china plates, as many cups and saucers, and one glass tumbler …

“These articles, with our camping outfit of camp kettles, long-handled frying pan, and Dutch oven, comprised all our household effects, with the exception of a broom that I forgot to mention.

“How often, while traveling through clouds of dust on the alkaline deserts, had I thought if I could only live to get into a cabin large enough to swing a broom, I would consider myself blest.

“Now I was the happy possessor of both cabin and broom. Where the soil was too gravelly to raise a dust—though I did not regret the lack of dust.

“We enjoyed the mild climate with its moist atmosphere—the average temperature making extremes of neither heat nor cold.

“During the rainy season, when sky and the beautiful landscape were obscured by the fog and clouds for days together, everything wore a gloomy aspect, but we soon became accustomed to the pattering of the gentle rain drops, and when the fog cleared away the blue sky and mountain scenery in the pure atmosphere were a feast for the soul.

“But for the unproductiveness of the gravelly soil, Grand Mound prairies would have filled my conception of an 'ideal home.'” (Phoebe Judson, pgs. 85-88).

“The prairie abounded with deer, the forest with grouse and pheasants, and the streams were alive with salmon and trout. …

“The Washington crab apple is about the size of the eastern cranberry. We often made marmalade of them in early days. After straining out the seeds and skins they had a very fine flavor. These crab apples, with very few native berries, was all the fruit we had for a number of years.” (Ibid, pg 89).

“We were comfortable all winter without glass in the windows, and when gathered around our fir bark fires in the large clay fireplace, with the children, our cabin was bright and cheerful.” (Ibid, pg. 95).

“We longed for spring, that we might make garden, having been so long without vegetables or fresh fruit, caused us to be exceedingly visionary in our plans for raising great crops the coming season; and our air castles, within whose walls were stacked potatoes, onions, cabbages, beets, peas and beans, towered high.” (Ibid, pg. 97).

“We never passed a more charming winter. It seemed more like a tropical, than a northern climate. A snowfall was of rare occurrence, and then only remained on the ground for a few days.” (Ibid, pg. 98).

“Bands of (Indians) frequently crowded into our little cabin, where, squatted on their feet, they would sit for hours enjoying our open fire, as well as our … bread, which, though so expensive, I always gave them on demand—because I was afraid to refuse them; while I, baby in arms, with Annie clinging to my side, stood near the door, which I kept wide open, in order to allow the odor from their filthy garments to escape, as well as an avenue of escape myself with the children, should they offer to molest us.” (Ibid, pg. 100).

“Mr. Judson plowed the garden, turning the wild grass under and the gravel on top, without fertilizing, for we had nothing to fertilize with—planted the garden seeds we had brought with us. He purchased a few seed potatoes, at something like five dollars per bushel, which gave us a delicious foretaste of our harvest for we ate the heart of our potatoes and planted the skins.

“The nuts and seeds for fruits and ornamental trees he planted in a small opening in the timber, where the soil looked more promising.

“After the gophers and squirrels had feasted upon them, and our garden bid fair to produce a crop of sorrel (a weed), in the place of vegetables, I began to fear this spot was not the ideal home about which I had built so many air castles.”

“To say the least, our prospects were not very flattering. The misfortune of not being able to raise a garden was a great disappointment to us … However, we were far from starvation, for game was plentiful, although I remember when a kind neighbor who had raised a good garden in the creek bottom gave me a few potatoes, I bedewed them with tears of joy as I carried them home in my apron. …

“The two pigs my father presented me met a deplorable fate. One of them died for the want of more milk, while the other, with all the milk, thrived vigorously … One day, while piggie was taking a nap by the doorway a great cougar stealthily crept out of the woods and nabbed him.” (Ibid, pg. 105-106).

The Indians were at first friendly, but tribes from east of the Cascades prevailed upon them to go to war to exterminate the whites. The summer of 1855 saw the beginning of the uprising, with many depredations made by the Indians upon the settlers. Stockades and forts were quickly erected, and the settlers from all around flocked to them. The McCornacks probably went to Fort Henness. “There were thirty families confined in Fort Henness, on Grand Mound ... This being a central fort, all the families from the surrounding country flocked into it, and here they lived for sixteen months, as thick as bees in a hive, and in perfect harmony, notwithstanding the fact that only a thin partition separated the families.” The harmony arose from the fact “that they were afraid the Indians would kill them and they wanted to die in peace with all mankind.” (A Pioneer's Search for an Ideal Home, by Phoebe Goodell Judson, pg. 165). Fort Henness housed 224 men, women, and children.

The Indian uprising, and the poor soil that the McCornacks found in their new home, were probably the inducements that led Andrew and Maria to think about going elsewhere. They had lived on and cultivated their 320 acres for the four years that the Donation Land Act required, so it was then possible for them to offer their homestead for sale. They determined to leave the Washington Territory, and to move south to the Oregon Territory.

Maria had given birth to Helen Isabella on 10 December 1854, during their second winter in the Washington Territory. Janet Maria arrived 3 February 1857 shortly after the Indian threats abated. The move to the West, in 1853, and the move to the Willamette Valley in 1857, were surely timed to be accomplished while Maria was not pregnant. By May 1859, when the next baby, Agnes, was born, the family was finally permanently settled west of Eugene. They had a fine farm of 700 acres.

Andrew raised wheat and livestock. Seven hundred acres was a huge amount of land to run considering that it was done with nothing more than horse- and man-power. But Andrew had many boys, and he used them. Grandfather Elwin A. McCornack described, in the following article, how the harvest was done, and then asked an extremely astute question at the end.

My Father's Day and Mine

“When my father was a young lad on the farm out west of Eugene he followed his father and four older brothers around the wheat field. Each carried a short steel sickle, and as the wheat fell from the blade, it fell onto the reaper's left arm; and when a sizable bundle had accumulated, the reaper bound it together with a wisp of the newly cut straw, dropped it in the stubble and swung his blade to start another bundle. Around and around the field, each reaper cutting right at the heels of the man next before him.

“Grandfather and his boys were harvesting the grain they had planted that the family might be fed. They knew of no other way of getting the harvest in. All men harvested just as they were doing. There was no other way. Looking back from where we stand today we see that they were practicing the identical method used by the reapers who labored in the field of Boaz where Ruth the Moabitess gleaned. The picture was the same. Thirty one hundred years had passed without any change in this most essential and much used process.

“When these bundles of wheat had lain out in the sun a sufficient time to cure and harden, Grandfather and the boys were again in the field, this time with oxen and wagons and hauled the bundles to the barnyard where they were piled in great weather proof stacks. Then when thrashing day came, the bundles were pitched down on the hard-beaten ground of the yard, and horses and oxen were driven around and around over the ground until the straw was separated from the wheat. Again we see the picture as no different than that of the Children of Israel thrashing out the grain on the thrashing floors of Pharaoh thirty five hundred years before.

“And Grandfather had told his sons of the trip to America from Scotland just a few years before. How they had made the crossing in a wind-driven sailing ship. Just such a ship as had bourn the venturesome Phoenicians on their voyages into the unknown world of two thousand B.C.

“Since those remote days the world had stood still with little change. Gunpowder, the printing press, yes, and a few of man's new ideas had come on the scene, but the progress of mankind and of the world was largely unchanged. It can truly be said that at the time my people came to the Oregon country the forward progress of man was still geared to the slow, measured tread of the oxen.

“Note now the things which have happened in my father's day and mine. Things which were unknown to an earlier generation. The new things which have come about. The list is limitless. The harnessing and uses of electricity. An understanding of the world of bacteriology and its uses in protecting human life. The telephone, the radio, television, radar. The use of steam and the railways. Petroleum and its thousand uses. The airplane and its world-wide service. Each one of these innovations and a hundred more has stepped up the pace at which the world is moving from the four miles an hour tread of the ox to a fantastic speed much faster than that of sound. Why has all this come to pass in our time? Why was it that God in his infinite wisdom did permit the world to stand still for three thousand years and then in your time and mine pull the plug as it were and permit the world to rush to its full and final destiny? That is truly the sixty-four dollar question of our day.” (Elwin A. McCornack, about 1938).

Andrew and Maria prospered at Eugene. They wrote glowing letters to their family back in Elgin, Illinois, and finally prevailed upon Maria's brother, Stewart Bates Ea kin, to make his own move to Eugene. He proposed to bring their parents with them. Stewart and his parents sold everything that they could, and converted it to cash. This he took to the bank, and exchanged it for a letter of credit, the theory being that they could use the letter of credit to purchase property and a place to live when they reached Oregon.

When Stewart and his family, and Robert and Margaret Eakin, finally reached Eugene in the fall of 1866, Maria and Andrew were overjoyed to see them. They welcomed them into their home, and Stewart immediately set out to find his own place to settle. He wanted a proved-up homestead. There were lands and homes to be purchased, but he found that no one was willing to take his letter of credit in payment. How would the seller get the money from a bank way back east? How would the money be safely transported? How many months would it take? What were the odds that the money would ever reach them?

It was almost an insurmountable problem, but Andrew came to the rescue. He had prospered enough that he was able and willing to cash the letter of credit. We don't know how he was eventually able to turn the letter of credit into cash for himself, but the story says much about his industry and about his success in the new country.

The McCornacks set off for the Puget Sound area of the Oregon Territory in April 1853. They may, or may not, have known that the Washington Territory had been partitioned off and formed in March, just before they left. In 1857 they moved to the Oregon Territory. On 14 February 1859 Oregon became the 33rd state of the Union.

In December 1865 Oregon's governor called a special session of the legislature, giving them these instructions: “The principal object for which I have called you together is to recommend that you adopt the amendment to the Constitution of the United States, proposed by the last session of Congress for the purpose at abolishing slavery wherever it exists in the United States."

The amendment referred to is the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and was duly ratified by both branches of the Legislature during this session. Andrew McCornack was the representative sent to that session by Lane County.

It is interesting to note how quickly political winds can shift. Prior to the Civil War, which began in 1861, Oregon was a hotbed of political strife concerning the question of slavery. The Democratic party was adamantly in favor of slavery, and wanted Oregon to be a slave state. The Democratic party was in the dominant position in Oregon as demonstrated by the makeup of the two legislative bodies. Of the 34 members of the House of Representatives in 1860, 24 were Democrat, and 10 were Republican. In the Senate, 13 were Democrat, and 3 were Republican. The Civil War had not yet begun.

The legislature apparently did not meet in 1861. When they next met in 1862, the Civil War was in full swing, and sentiments had swung to the other end of the spectrum. Of the 34 members of the House of Representatives, only one was Democratic, and 33 were Republican. In the Senate, 5 were Democratic, one was Independent, and 10 were Republican. That balance was still prevalent when Andrew McCornack was serving in 1865, just after the end of the war. There were 5 Democrats serving in the House, and 34 Republicans, of which Andrew was one.

I must now comment upon our parentage. Our grandfather was Elwin A. McCornack. His father was the baby that Maria brought across the plains, Herbert Fraser McCornack. Elwin's mother was Ellen Condon, the second child born to Thomas and Cornelia Condon in 1855 in Forest Grove, Oregon Territory. The McCornack and Condon families came to the Oregon Territory in the same year, 1853. One came by ship, the other by wagon. Neither family had anything except the bare essentials, and a firm belief that with God's help, they could accomplish anything.

The McCornacks eventually had 12 children, and raised them all. The Condons had 10, losing three babies, and their prized and eldest son at the age of 18. Both families were firm believers in education. Education was a high priority. All the children got as much education as they could, and all became respected and successful pillars of their communities. Eight of the 12 McCornack children graduated from college. For that day and age, that is an astounding accomplishment. Daughter, Mary, was even sent to attend the New England Conservatory of Music. How were the educations and the travel financed?

I'd like to think that it was God's own hand that caused these two families to uproot themselves, to move across a continent, and to be brought together in the primitive, sparsely-populated wilderness that was the Oregon Territory. Ellen, the college graduate, and Herbert, the doctor, were noble people. So were their parents. So was their son, Elwin. There were none better. They were our ancestors. They came when times were hard. They paved the way. Any blessings, comforts, freedoms, or futures that we have are because of them. We'd do well to remember that and them.

It was at Eugene that Herbert and Ellen became acquainted.

It is in Eugene, in the Masonic Cemetery, that all of these people are buried. There are five couples:

Robert Eakin, 1786-1876, and Margaret Bates Eakin, 1786-1875.

Andrew McCornack, 1817-1872, and Maria Eakin McCornack, 1825-1902.

Thomas Condon, 1822-1907, and Cornelia Holt Condon, 1832-1901.

Herbert Fraser McCornack, 1852-1916, and Ellen Condon McCornack, 1855-1929.

Elwin A. McCornack, 1883-1962, and Bernice Adams McCornack, 1883-1946.